Approximate Read Time: 10 minutes

“When rehab gets chaotic, organize by movement vectors. Pick the day’s vector, align every drill to it, and lean into coherence to improve efficiency.”

What You Will Learn

- Why movement vectors (vertical, linear, lateral) are a simple organizing principle that reduce complexity and create coherence

- How to apply the 3P Model—Principles, Process, Plans to vector-based rehab so daily decisions are consistent, measurable, and adaptable

- How to progress rehab using the force–velocity curve to target specific athletic qualities within each vector.

Muscle Integration into Movement Vectors

Every sport may look different, but the underlying movement patterns are consistent. Then again, we are all humans with two feet and two hands, right? But rehab design can become overwhelming with all of the differing movement philosophies and training paradigms.

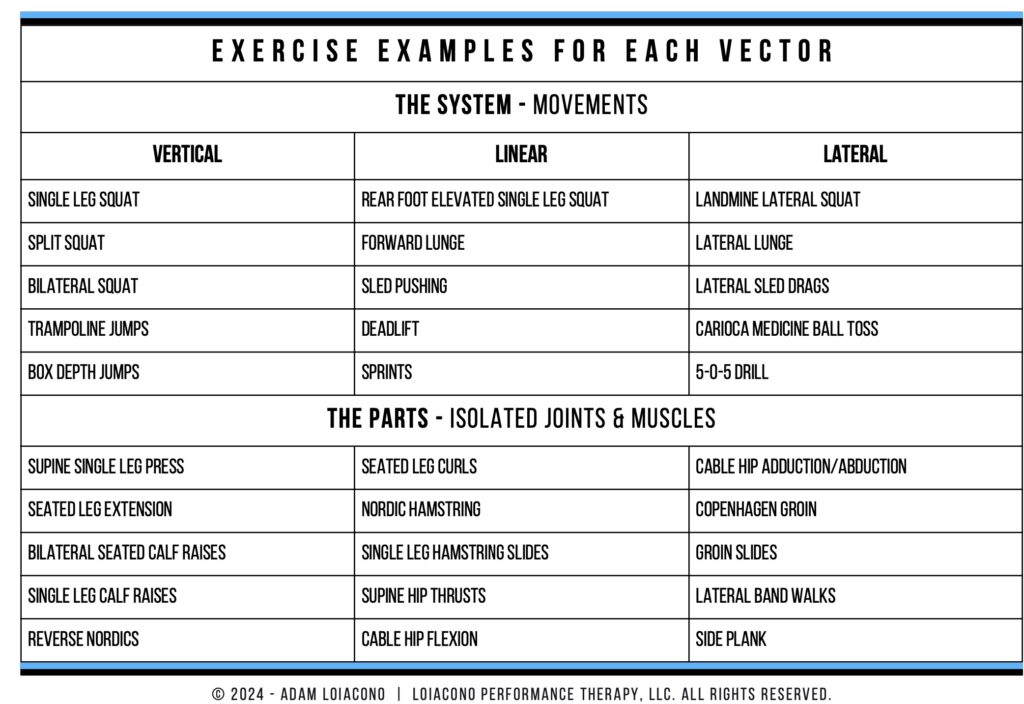

The solution? Grouping stress into three movement vectors: vertical, linear, and lateral. This turns the chaos into a clear framework for loading, recovery, and adaptation.

- Vertical = jumping and jump landing

- Linear = sprinting and running straight ahead

- Lateral = agility and changing directions

Each vector not only emphasizes a specific global movement (the system), but also variable muscle groups and tissue stress (the parts):

- Vertical → quadriceps, gastrocnemius/soleus

- Linear → hamstrings, glute max, hip flexors

- Lateral → adductors/abductors, obliques

When you assign a day to a single vector, you instantly simplify selection. start with the system (global task) and finish with the parts (local tissue). The session reads like a sentence rather than a list. That logic brings about coherence and keeps progression predictable and repeatable.

3 primary movement vectors

Think of each training day as a sentence with a single subject being the vector. Start by expressing the big idea with a system (movement) that captures the day’s force and posture demands, then punctuate it with parts (joints/muscles) that work to target the specific tissues that support that movement. Here’s how that looks in practice:

Physiological levers you’ll pull

Classic periodization models – block, undulating, or microdosing – focus on sets, reps, and volume progression. Movement vectors compliment these models by progressing the parts and system of specific movements.

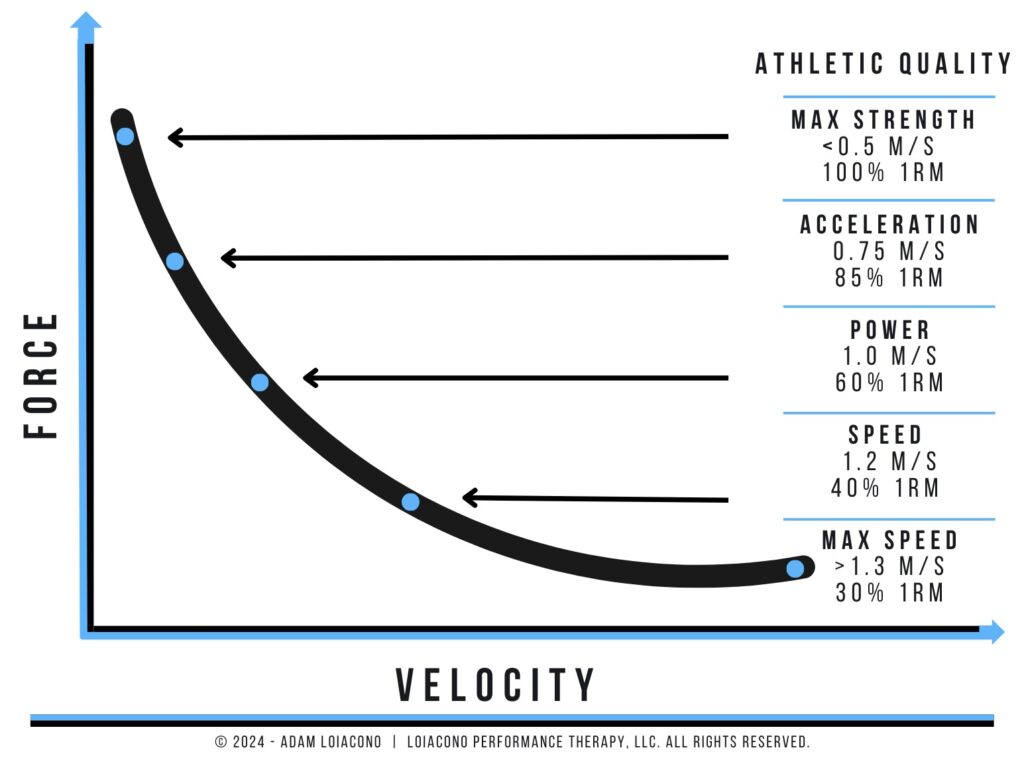

The force–velocity (F–V) curve is the map of how speed and strength trade places as load changes. Slow and heavy for maximal strength versus fast and light for speed. In rehab, using the curve intentionally keeps loading progressive and directional.

- Slow speeds + heavy loads = muscle hypertrophy + motor unit recruitments

- Fast speeds + light loads = tendon stiffness + rate coding

Managing adaptation means learning to adjust the dials of load, volume, rest, and velocity. The ACSM Position Stand (Ratamess, 2009) gives clear targets for each of strength, hypertrophy, endurance, and power that can be translated directly into your vector days. Once initial symptoms and pain reduce, then we can periodize these stressors across blocks or undulations. Adequate periodization – either undulating or block – will consistently outperform random progression (Issurin, 2016).

Decision-Making

Ask yourself this – does every exercise on the page serve the vector of the day? If not, remove it from the day. That’s coherence.

With any injury there are movement and loading constraints throughout the rehab process. An early ankle sprain rehab is going to be limited in the lateral vector because of the compromised stability of the lateral ankle ligaments.

When we understand these constraints (tissue status, provocation positions, positional demands), we can use them to prioritize a single vector per working day. For example, if I have a lateral ankle sprain, my highest priority vector will be lateral because the ability to change direction efficiently requires end range supination under load. This is very challenging for the lateral ankle ligaments.

Vice versa, sprinting and jumping do require the foot and ankle complex, but in a different manner. These vectors require plantar flexion and dorsiflexion – two motions that do not stress the lateral ankle ligaments as much. Now that we have prioritized which vectors are a priority, we can eliminate the noise and prioritize our decisions.

- Pick one system (movement) that trains the vector.

- Pick two parts (single joint or muscle group) to support the movement.

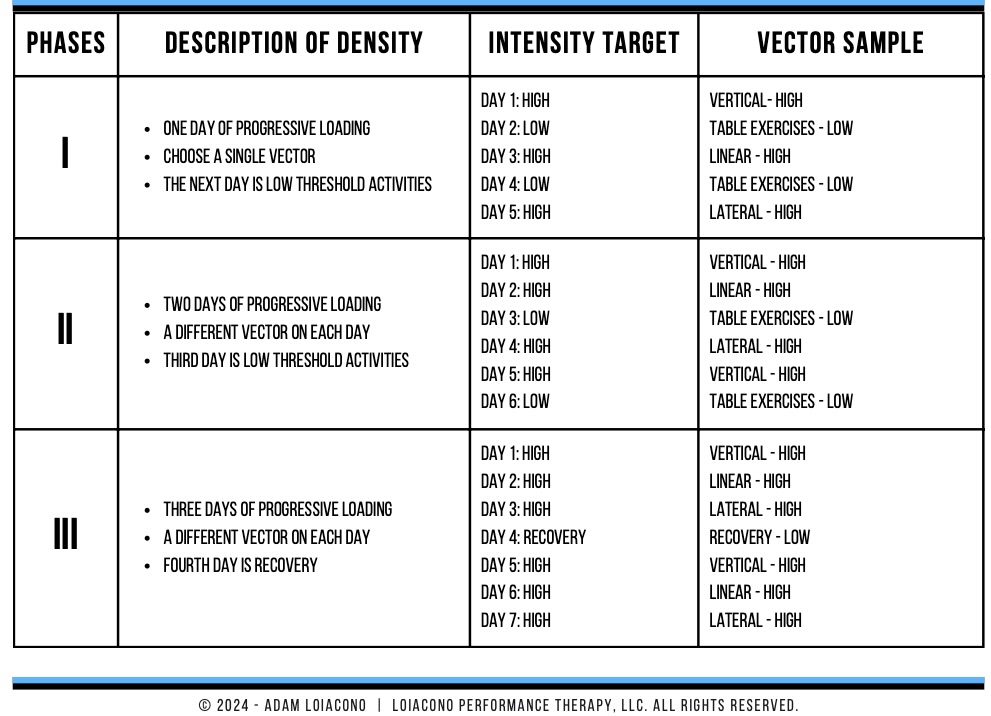

- Cycle density (load × frequency) via high/low day to allow for adequate recovery.

Keystone Barriers to Recovery

Rehab often fails not because of effort, but because of noise. Too many unrelated correctives scatter attention and dilute adaptation. Vector discipline restores focus by aligning every drill to a single purpose.

Rehab plans often forgo adequate development of absolute strength at the expense of achieving running and jumping milestones. This error will manifest itself as a “setback” when in actuality its more of an underprepared tissue from inadequate development of qualities. When we implement standards along the force–velocity curve then we create explicit staging from strength to power to speed that addresses each quality.

Finally, the rhythm of training matters as much as its content: living in “medium zones” is a no-man’s-land where you neither adapt nor recover. Alternating high and low density days gives the body clear signals to build and to rest.

Phases of Rehab: From Biology to Sport

Build movement capacity by vector, progress along the F–V curve, and cycle density high/low.

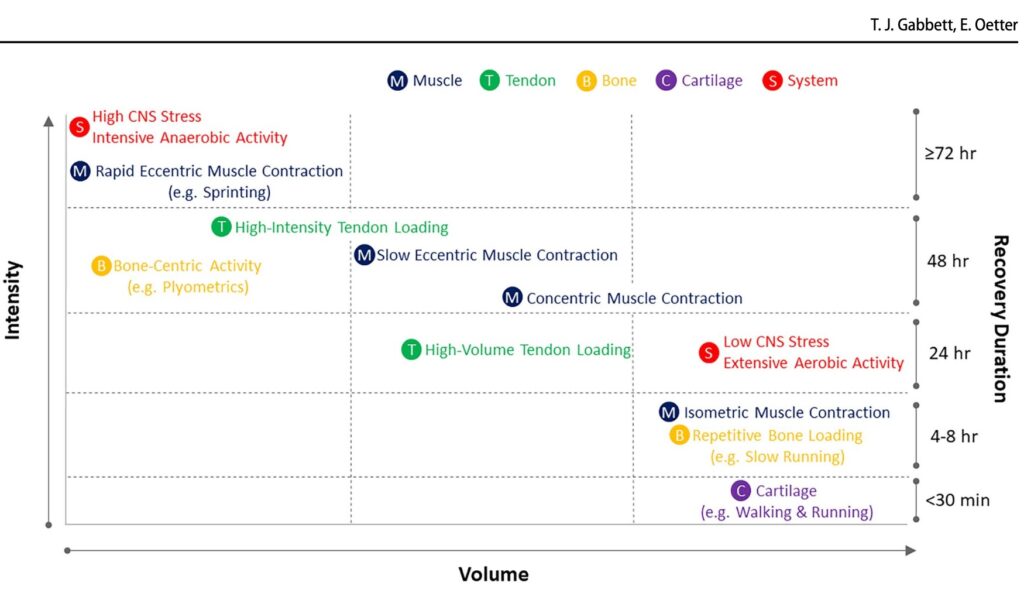

Good rehab isn’t just about movement rather it’s about timing biology. Each tissue heals and adapts on its own clock, so the structure of your program should mirror the physiology underneath it. When you organize progressions by vector, you also align them with how muscle, tendon, and joint tissues naturally recover and rebuild.

- Muscle recovers faster from concentric/isometric than from intensive eccentric stretch-shortening

- Tendon adapts to progressive heavy–slow + isometrics

- Cartilage/joint irritability → use systems work around the limb (bike, pool) to sustain fitness as tissue calms while keeping the system adapting.

Early Phase: organize + re-introduce

Medium is the enemy. Alternate high/low density. High to adapt, low to recover. Medium is not enough to create adaptation yet enough to require recovery.

Goal: Reduce nociception and swelling while rehearsing the vector’s shape at low thresholds. Accumulate isometrics → tempos → short ROM where needed. This is where table exercises and machines can be valuable.

- Vertical day (example)

System: leg press, tempo 3–1–3.

Parts: Seated knee extension; bilateral calf raise isometric (45–60 s).

Loading notes: 30–50% 1RM range, 2–4 sets, rest 60–90 s; slow intent. - Linear day (example)

System: Wall marching drills; Split squats

Parts: single leg glute bridges; cable or banded hip flexion - Lateral day (example)

System: Lateral landmine split squat; Pallof press

Parts: Copenhagen ISO (short lever); half kneeling chop/lift

Density: High–Low over 3-day micro: Day 1 high (chosen vector), Day 2 low (table work), Day 3 high (repeat or new vector).

want to learn more about density? CHECK OUT THE FULL ARTICLE HERE!

Middle Phase: load capacity + expand Range of Motion

Goal: Progress force and rate within the vector; evolve isometric → dynamic → velocity and continue to progress open and closed chain.

Periodization guidelines (novice–intermediate): 60–70% 1RM (8–12 reps), 1–3 sets initially; for power, lighter loads moved fast; rest 2–3 min for main lifts.

- Vertical day (example)

System: Trap-bar deadlift (from blocks), 3×5 @ ~70–80%, 2–3 min rest

Parts: Knee extension (controlled, 2–0–2), seated calf raises (heavy).

Introduce low-amplitude pogo (extensive, sub-max ground contacts). - Linear day (example)

System: Sled push (20–30 m @ bodyweight × 0.5–0.75); short A-Skpis (10 – 15m)

Parts: Nordic hamstring (eccentric-biased); hip thrust 3×8. - Lateral day (example)

System: Lateral landmine squat 4×6; lateral sled drag.

Parts: Copenhagen progressions; adduction slides.

Density: Two high days + 1 low (motor learning/table). Rotate vectors so each appears 1–2×/wk.

Late Phase: reactivity + top-end outputs

Goal: Add intensive stretch-shortening work, COD speed, and sport-specific postures by vector, ensuring adequate chronic load base.

- Vertical day → Depth drops (low height), then rebound jumps; progress squats to fast dynamic efforts (≤60% at speeds 1.0 – 1.3 meter/second)

- Linear day → Fly-in sprints, upright mechanics; light resisted/assisted runs

- Lateral day → Planned reactive COD; curvilinear runs; eccentric-biased adductor work maintains tendon capacity.

Density: Keep high/low alternation of intensive plyo/COD days followed by low-threshold tissue care or table work.

Sport Phase: embed testing + standards

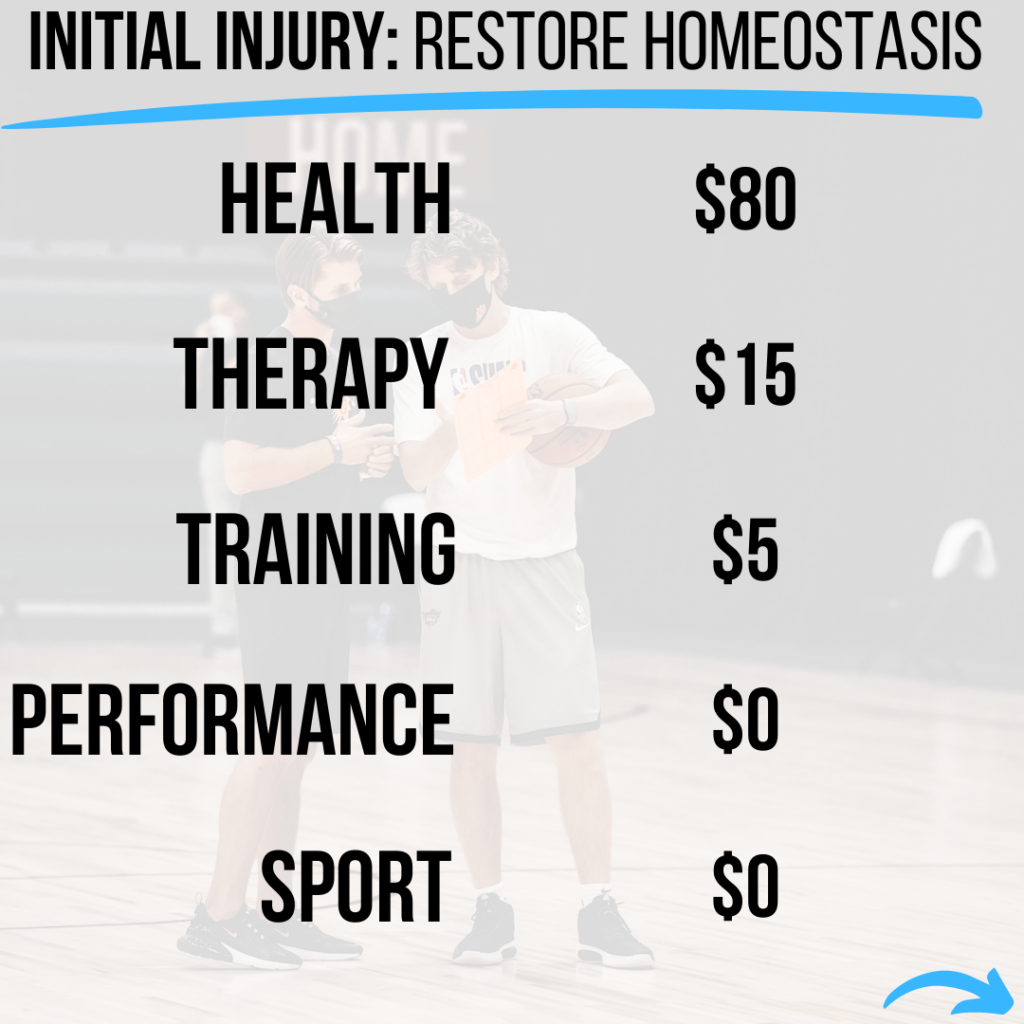

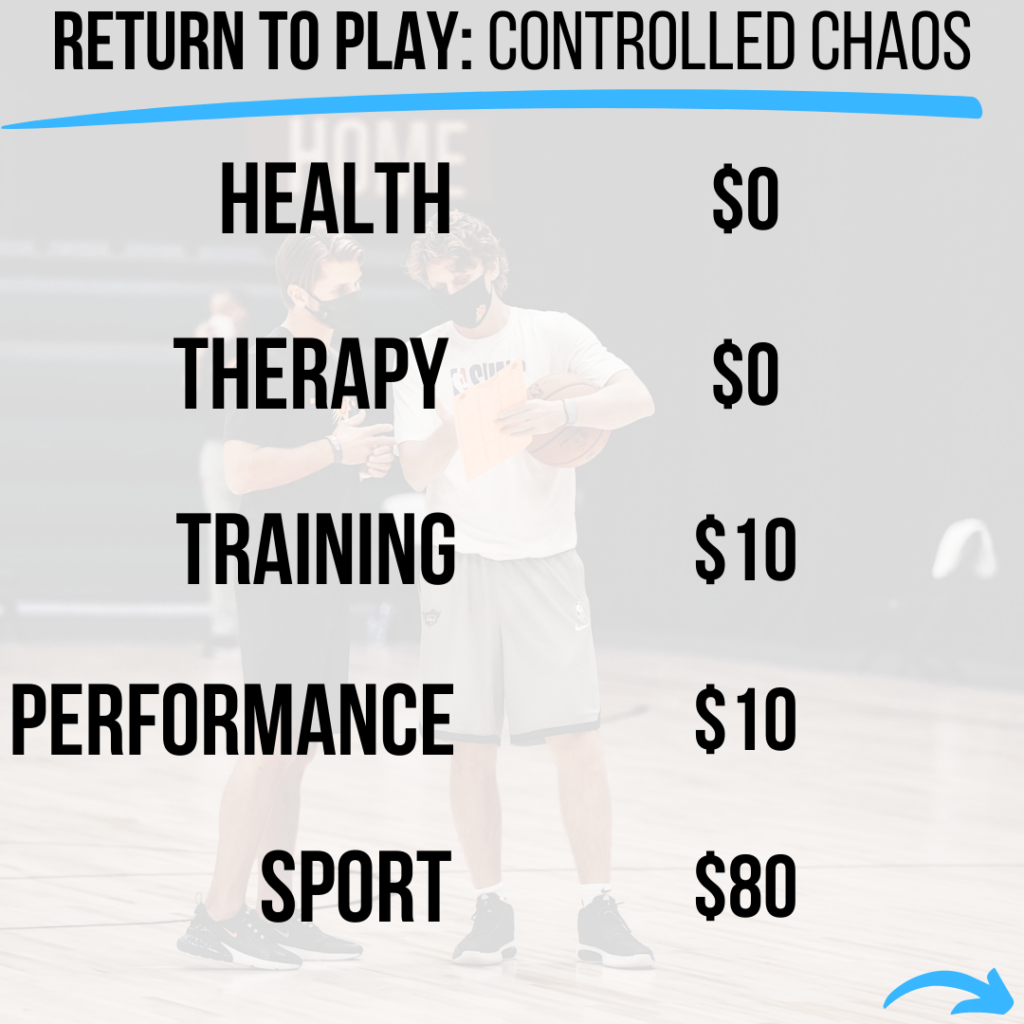

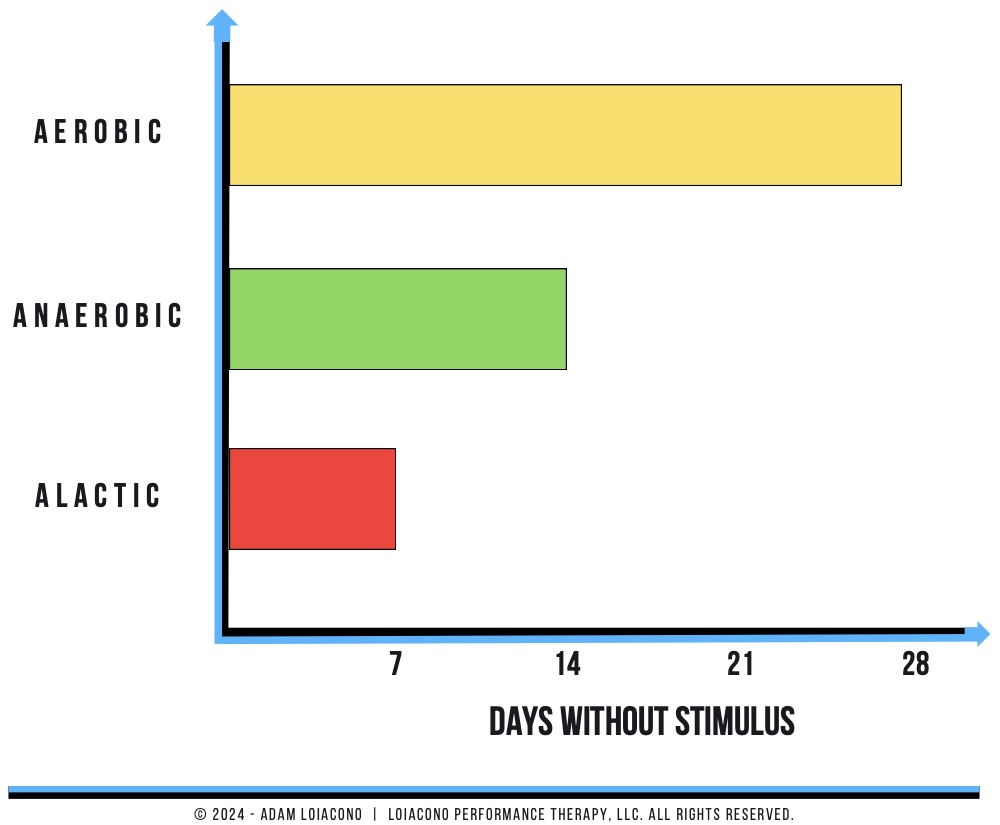

Use embedded testing weekly to confirm that your vector outputs are maintaining while the athlete continues to participate in sport. Remember THE BANK – there are only so many resources available especially as sport participation starts to increase. Movement vectors and objective feedback loops become the foundation to efficient decision making.

You can also guide density using residuals by how long qualities persist when not trained so you don’t let certain qualities go untrained while emphasizing others. See Residual Training Effects: How Long Training Programs Last.

3 Common Mistakes & Pitfalls

Even well-intentioned rehab program can stall when structure fades. The most common errors in rehab aren’t about the exercises themselves rather they’re about how they’re organized and sequenced. These are the classic traps that break coherence and blunt adaptation.

- Medium-every-day density: no adaptation, no recovery. Use high/low.

- Exercise soup: good drills, no coherence. Every choice must serve the vector.

- Skipping the slow end of F–V: you don’t regain sprint outputs when the force foundation is missing. Embrace the struggle of absolute and max strength training.

Integration with the 3P Framework

The 3P Framework—Principles, Process, and Plans is the scaffolding that holds every vector-based progression together. It turns the art of rehab into a repeatable system, linking what you believe, how you experiment, and what you ultimately execute. Within this structure, each vector day becomes a living application of the 3P Model: guided by principles, refined through process, and organized into repeatable plans.

Principles → Coherence through clarity: coherence begins with the sub-principle of prioritize and simplify by selecting one movement vector per day (vertical, linear, or lateral) so every exercise shares a clear intent. This honors the 3P principles of coordinating movement and managing force while eliminating noise from unrelated correctives.

Process → Coherence through experimentation: use gradual exposure and test–retest loops within each vector to gauge readiness. For instance, progressing a vertical vector from isometric to dynamic to plyometric loading mirrors the experimental rhythm of the Process pillar—adjusting plans based on data and clinical presentations.

Plans → Coherence through structured density and progression: periodize load, density, and recovery by vector—high/low density cycles and force–velocity staging form the backbone of progression. This creates a plan that is logically consistent across sessions. Each week’s design builds directly from the previous ensuring the system (global movement) and parts (local tissues) evolve in unison.

Conclusion

Movement vectors in rehab give you an immediate organizational lens though vertical, linear, and lateral so each day is coherent and progressive. Combine vectors with the force–velocity curve and periodized density, and your plans become both simple and adaptable. The 3P Model keeps you honest: principles to decide, process to adapt, plans to execute. That’s how you move from chaos to clarity and athletes feel the difference because their sessions are efficient and progressive.

5 Keys to Movement-Vector Rehab

- Test → adjust: embed small KPIs each week.

- Choose one vector per day and align system → parts to it.

- Climb the F–V curve: strength → power → speed.

- Cycle density high/low; never live in the middle.

- Periodize late stage—variation beats monotony.

Free Download

Watch More Like This

Read More Like This

Related Podcasts

References

Ratamess NA, Alvar BA, Evetoch TK, et al. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(3):687–708.

Iversen VM, Norum M, Schoenfeld BJ, Fimland MS. No time to lift? Time-efficient training programs for strength and hypertrophy. Sports Med. 2021;51:2079–2095.

Williams TD, Tolusso DV, Fedewa MV, Esco MR. Comparison of periodized and non-periodized resistance training on maximal strength: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47:2083–2100.

Issurin VB. Benefits and limitations of block periodized training approaches: a review. Sports Med. 2016;46:329–338.