Approximate Read Time: 9 minutes

“Stem cells for knee osteoarthritis may not just manage pain—they may regenerate cartilage and extend joint health.”

What You Will Learn

- How umbilical cord-derived stem cells regenerate cartilage in knee osteoarthritis.

- Clinical trial outcomes comparing stem cells with BMAC and microdrilling.

- Long-term safety, efficacy, and integration into the 3P Framework for rehab.

Why Stem Cells Matter for Knee Osteoarthritis

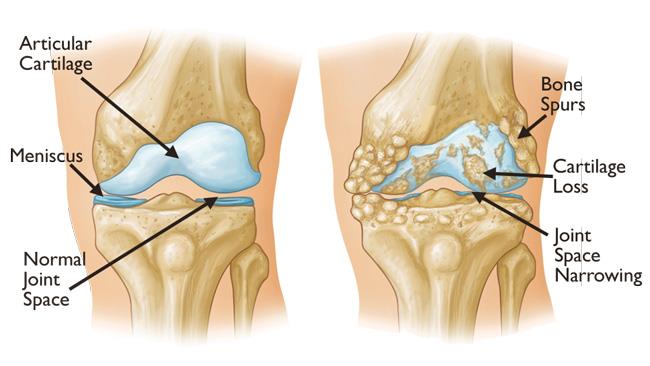

Knee osteoarthritis is one of the most common causes of chronic pain and disability worldwide. For decades, treatment has been more about managing symptoms than reversing the disease. Pain medications, cortisone injections, hyaluronic acid, and even arthroscopic procedures can help, but only temporarily. None truly address the underlying loss of cartilage, the slippery surface that allows the knee to move with ease.

Cartilage has almost no natural capacity to heal. Once it’s gone, it’s gone—at least that’s what many experts believed. The emergence of stem cell therapies, particularly those derived from umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells (hUCB-MSCs), has begun to challenge that assumption.

These therapies are not just about pain control. They may actually stimulate cartilage regeneration, change the biology of the joint, and potentially delay or even prevent the need for joint replacement surgery.

The Science Behind Umbilical Cord Stem Cells

Stem cells are like a foreman for a construction site. The foreman doesn’t lay the bricks but organizes the crew, delivers instructions, and ensures the building gets completed.

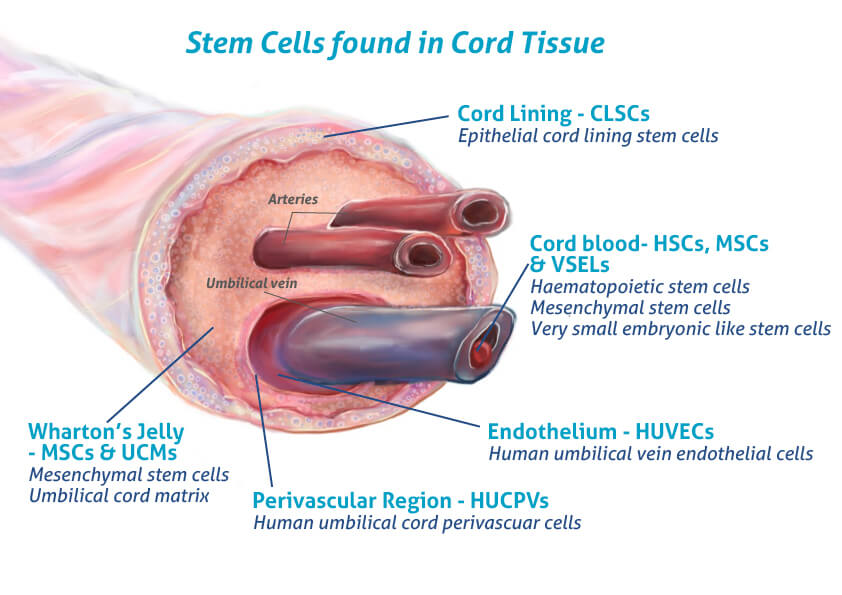

Stem cells are often described as the body’s raw materials—cells capable of developing into different types of tissues. What sets umbilical cord blood stem cells apart is their unique combination of availability, potency, and safety.

Unlike bone marrow or adipose-derived cells, cord blood cells are collected non-invasively, after birth, from tissue that would otherwise be discarded. They are highly proliferative, meaning they can multiply rapidly, and they show a strong ability to promote cartilage-like tissue. Perhaps most importantly, they are hypoimmunogenic. This makes them less likely to trigger an immune response, even when used in an allogeneic (donor-to-patient) setting (Lee, 2022).

These cells don’t necessarily turn into cartilage themselves. Instead, they release signals—cytokines and growth factors—that recruit the body’s own cells and encourage them to repair damaged areas. It’s like hiring a foreman for a construction site. The foreman doesn’t lay the bricks but organizes the crew, delivers instructions, and ensures the building gets completed.

Early Evidence: The Park Trial and Cartistem

One of the first major clinical trials to capture attention was conducted in South Korea in 2017. Park and colleagues tested a therapy called Cartistem®, a combination of cultured umbilical stem cells and hyaluronic acid gel, in patients with advanced knee osteoarthritis.

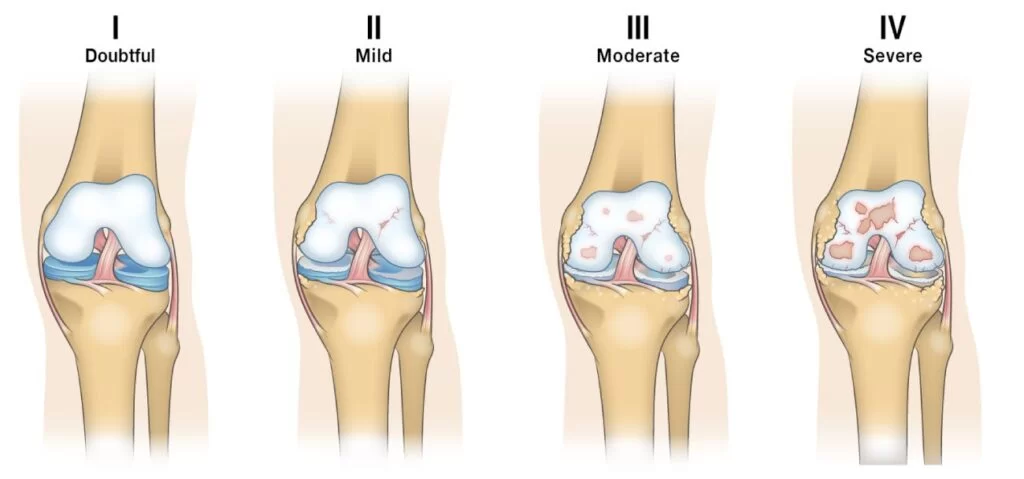

The participants were not mild cases. They had grade 3 osteoarthritis and grade 4 cartilage defects, meaning significant loss and damage. Surgeons implanted the stem cell gel directly into the lesion sites.

At three months, early repair tissue was already visible during arthroscopy. By one year, biopsy samples showed hyaline-like cartilage, the gold standard tissue type in healthy knees. Seven years later, patients still reported better pain and function scores, and importantly, there were no cases of tumor formation or severe side effects. This was one of the first clear demonstrations that stem cells could safely produce long-lasting, biologically meaningful repair (Park, 2017).

Stem Cells vs. Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate (BMAC)

Bone marrow aspirate concentrate, or BMAC, has long been used in sports medicine and orthopedics. It’s derived from a patient’s own bone marrow, concentrated, and injected back into the joint. While safe, BMAC as limitations as the number of stem cells declines with age.

A 2021 study by Yang and colleagues compared BMAC to umbilical cord stem cells in patients undergoing high tibial osteotomy, a surgery that shifts weight-bearing away from damaged cartilage. Both groups experienced improvements in pain and function. But when surgeons looked at the cartilage directly through second-look arthroscopy, the umbilical cord stem cell group showed more complete and higher-quality regeneration (Yang, 2021).

This finding has been echoed in other trials and reviews: while BMAC may help symptoms, umbilical cord stem cells appear to produce a stronger structural repair.

Meta-Analysis: Evidence Across Hundreds of Patients

To understand the broader picture, systematic reviews and meta-analyses are crucial. In 2022, Lee and colleagues analyzed seven studies with more than 500 patients treated with umbilical cord stem cells for knee osteoarthritis.

Across the board, patients reported significant reductions in pain (VAS scores), better function (IKDC and WOMAC scores), and improved quality of life. Imaging and arthroscopic findings confirmed that these clinical benefits were supported by actual cartilage regeneration. Importantly, the therapy maintained a strong safety profile—no severe adverse events, no tumorigenesis, and only occasional mild, transient swelling (Lee, 2022).

The authors concluded that umbilical cord stem cells are both effective and safe, though they emphasized the need for longer follow-up studies and comparisons to other biologics.

Stem Cells vs. Microdrilling: A 2024 Trial

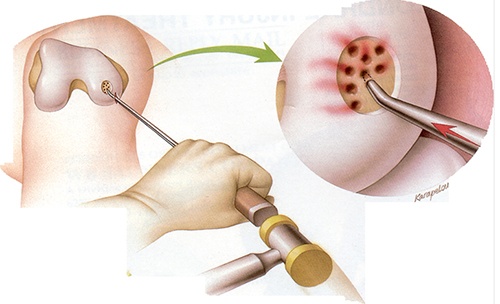

Another key comparison is with microdrilling, a surgical technique designed to stimulate marrow bleeding and promote fibrocartilage growth. While this can work in the short term, the fibrocartilage produced often lacks the durability of hyaline cartilage.

In 2024, Jung and colleagues published a trial that directly compared microdrilling with umbilical cord stem cell implantation in patients undergoing high tibial osteotomy. At two years, both groups felt better, but the stem cell group reported superior pain relief and function on standardized knee scores. Second-look arthroscopy revealed healthier, smoother cartilage surfaces in the stem cell group.

Interestingly, location mattered. Lesions at the front of the knee (anterior lesions) healed more successfully than those further back, suggesting mechanical environment plays a role in outcomes (Jung, 2024).

Safety and Long-Term Outcomes

Safety is always the first concern in regenerative medicine. Across multiple trials and systematic reviews, umbilical cord stem cells have demonstrated a reassuring profile.

No studies have reported tumor formation or inappropriate bone growth. The most common side effects are temporary swelling or discomfort, which typically resolve without intervention (Dhillon, 2022). In the seven-year follow-up from Park’s trial, no participants required knee replacement, and pain/function improvements persisted over time.

Still, it’s important to note that most of these studies have been conducted in Asia, particularly South Korea, where Cartistem is approved. In the United States, expanded allogeneic stem cells are not yet FDA-approved, and most clinical use remains limited to trials or international clinics.

How Stem Cells Compare to Other Biologics

Stem cells are not the only biologic option for knee osteoarthritis. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and hyaluronic acid injections are widely used, but their effects are temporary and primarily anti-inflammatory. BMAC offers an autologous solution but provides limited stem cell content, especially in older patients.

| Source | Advantages | Limitations | Clinical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone Marrow | Strong osteogenic potential; most studied | Harvest invasive; cell yield decreases with donor age | Effective in bone/cartilage applications |

| Adipose Tissue | High yield; easy to harvest; proliferates longer | Variable chondrogenic capacity | Good option for tendon/soft tissue |

| Wharton’s Jelly | “Younger” cells; immune-privileged; reduced rejection | Dependent on donor screening; less standardized protocols | Increasingly used in systemic infusions |

Umbilical cord stem cells combine the best of both worlds: high proliferative capacity, potent regenerative signaling, and consistent quality. In head-to-head comparisons, they have produced stronger cartilage regeneration than both BMAC and microdrilling, while offering more durable outcomes than PRP (Yang, 2021).

Integration with the 3P Framework

In my own work as a performance therapist, I emphasize that biologics are not a standalone cure. They must be integrated into a structured rehabilitation framework.

The 3P Model—Principles, Process, Plans—offers exactly that.

- Principles: Respect tissue healing timelines. Cartilage repair is slow, so aggressive loading too soon undermines results.

- Process: Use test–retest methods, embedded testing, and progressive exposure. Monitor swelling, IKDC scores, and functional metrics to guide advancement.

- Plans: Surround the biologic intervention with comprehensive training. When the joint itself must be protected, systemic fitness can be maintained with alternatives like swimming, cycling, or upper-body conditioning.

Stem cells may create the biological foundation, but it’s through careful rehab that athletes and patients return to full performance.

The Future of Stem Cells for Knee Osteoarthritis

Looking ahead, several innovations are on the horizon. Exosome therapy—using the vesicles secreted by stem cells rather than the cells themselves—may deliver regenerative signals with fewer regulatory hurdles. Combination therapies, such as stem cells with scaffolds or repeat dosing strategies, are being explored.

The evidence base is growing quickly. Long-term studies now extend up to seven years, and multiple systematic reviews show consistent benefits. Still, questions remain about optimal dosing, patient selection, and cost-effectiveness. In the United States, there also is the significant hurdle of overcoming misinformation and lack of understanding of the healing potential of stem cells.

For now, umbilical cord stem cells stand as one of the most promising tools for patients with knee osteoarthritis who are looking for more than temporary relief.

Conclusion: A Regenerative Step Forward

The story of stem cells for knee osteoarthritis is still being written, but the chapters so far are compelling. Clinical trials demonstrate durable improvements in pain and function. Histology and imaging reveal true cartilage regeneration. Safety remains strong.

No therapy is perfect, and stem cells are not a magic fix. But when paired with smart rehabilitation, they may change the trajectory of knee osteoarthritis from a one-way decline to a condition that can be managed—and in some cases, reversed.

For clinicians, coaches, and patients, the message is clear: stem cells are not just about extending joint life. They’re about restoring movement, protecting performance, and offering hope where little existed before.

Read More Like This

Related Podcasts

References

- Park YB, Ha CW, Lee CH, Yoon YC, Park YG. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6(2):613–621Cartilage regeneration in osteo….

- Yang HY, Song EK, Kang SJ, et al. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021;29:208–218MSCuc superior to BMAC for cart….

- Lee DH, Kim SA, Song JS, et al. Medicina. 2022;58(12):1801Systematic Review and Meta Anal….

- Jung SH, Nam BJ, Choi CH, et al. Sci Rep. 2024;14:3333UBC MSC vs microdrilling combin….

- Dhillon J, Kraeutler MJ, Belk JW, Scillia AJ. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022;10(7):23259671221104409Umbilical_Cord-Derived_Stem_Cel….