Approximate Read Time: 8 minutes

“Residual training effects are critical to understand for efficient, athlete programming. If you understand these effects, then athletes will continue to make progress towards goals.”

What You Will Learn

- What residual training effects are and why they matter

- How long key qualities last without training

- How to apply residuals in-season, offseason, and rehab

Why Residuals Matter More Than Ever

In high-performance sport the calendar is tight and the travel is relentless. Most weeks you’re not asking, “What can I add?” rather “What can we scale back?” That is the practical genius of Residual Training Effects (RTE): knowing how long a quality persists after you stop directly training it, so you can emphasize one target today without losing another tomorrow (2016, Issurin).

Vladimir Issurin created block periodization, concentrated training on a small number of compatible qualities, then sequence blocks so the right effects overlap at the right time (2016, Issurin). Residuals are the glue between those blocks. They’re also the antidote to the modern athlete’s reality: games stacked, practices squeezed, and windows for quality work measured in minutes, not hours.

Behind all of this is an underlying message from Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS). GAS is the day-to-day operating system: stress → alarm → resistance → (mismanage it) exhaustion (1950, Selye).

By the Numbers: A Working Definition

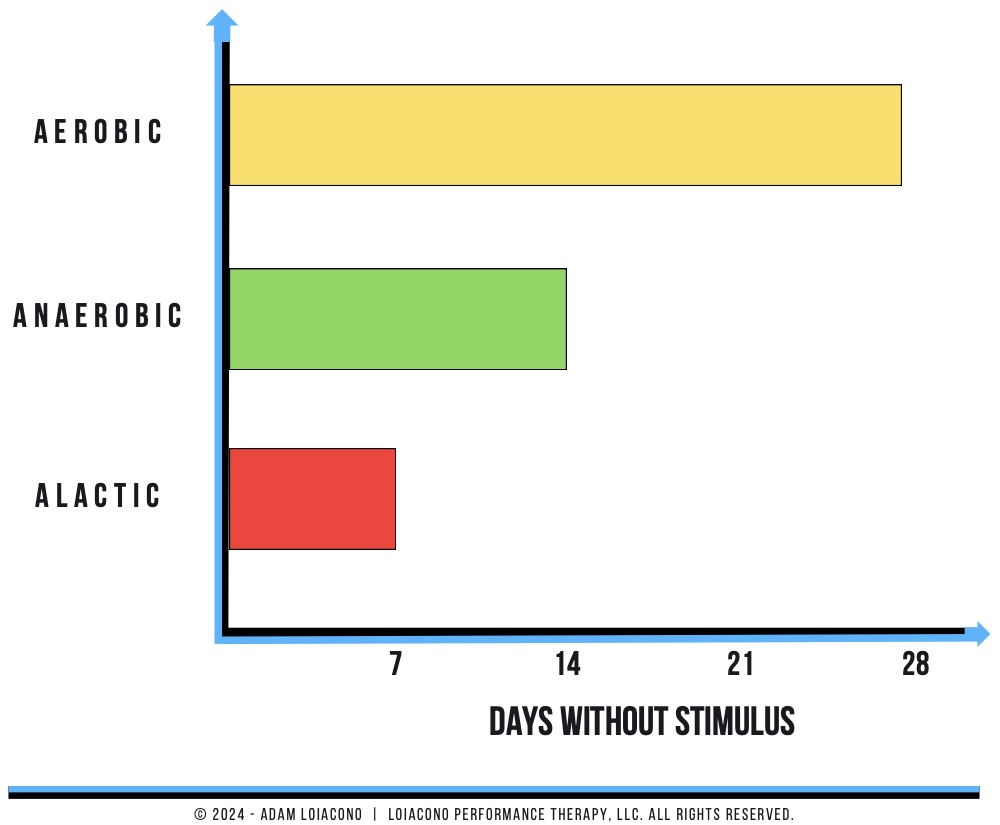

Residual Training Effects describe how long a performance quality is retained after you reduce or remove the specific stimulus that built it (2016, Issurin). The values below are practical ranges and guardrails, but they reliably inform choices when the calendar constrains you.

- Aerobic capacity: ~30±5 days

- Max strength: ~30±5 days

- Anaerobic glycolytic: ~18±4 days

- Power: ~15±5 days

- Alactic/PCr: ~5±3 days

- Speed: ~5±3 days

Strength and aerobic qualities can be placed on pause briefly while you focus on something else. Speed and phosophocreatine systems (PCr) cannot because of their shorter timelines. By understanding these key guidelines, decisions on what qualities to train when become easier and less complex.

The Physiology Behind the Residuals

These guidelines aren’t arbitrary. They track the biology underneath. Aerobic adaptations are structural such as mitochondria, capillary density, and left ventricle hypertrophy and they diminish slowly. Strength is a hybrid with structural adaptions in muscle cross sectional area plus neural adaptations with motor unit recruitment and synchronization.

Power will increase with strength, yet is more dependent on the neural components of motor patterns and muscle fiber recruitment. Speed is heavily biased toward neural and skill acquisition so this requires frequent refreshers. If we understand the physiology behind these timeline, then we can appreciate why certain characteristics require certain time intervals.

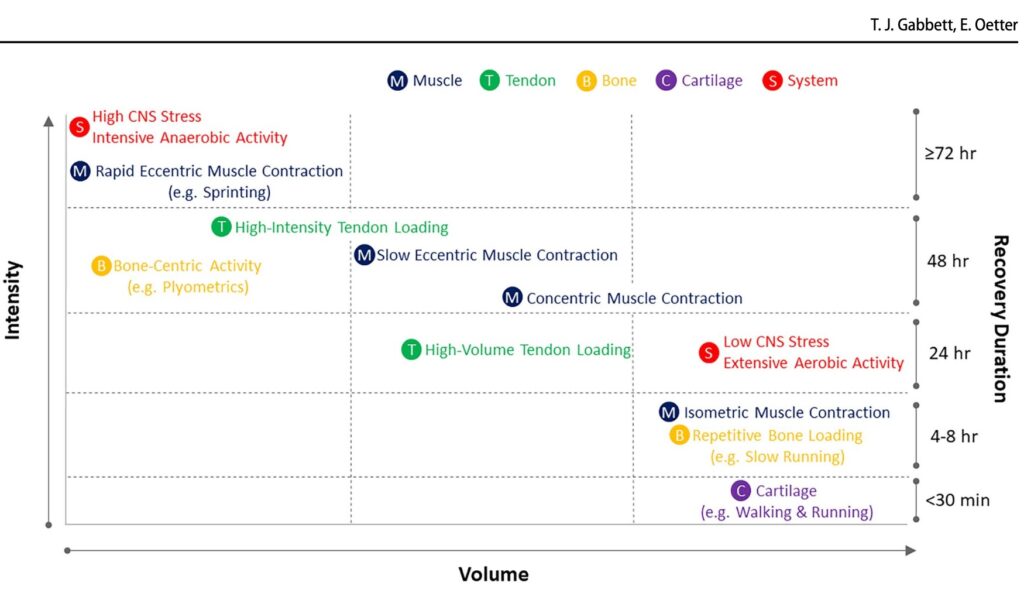

The tissue story matters too. Tendon, muscle, cartilage, and bone do not recover on the same timelines. High-velocity sprinting, for example, can alter tendon behavior for ~48 hours; cartilage may normalize within ~30 minutes under moderate load; bone cells desensitize after ~20 loading cycles and re-sensitize hours later. This is why polarizing stress, stacking high with high, protecting true low, is more beneficial than living in the middle (2024, Gabbett & Oetter).

The Promise and the Trap of Residuals

The promise is clarity. Residuals tell you what can wait 10–14 days (strength, aerobic) and what must be trained every 3–5 days (speed). They help you sequence blocks with fewer interference effects. They reduce the sense that you must train everything all the time.

“Residuals tell you what you can skip today, not what you can ignore.”

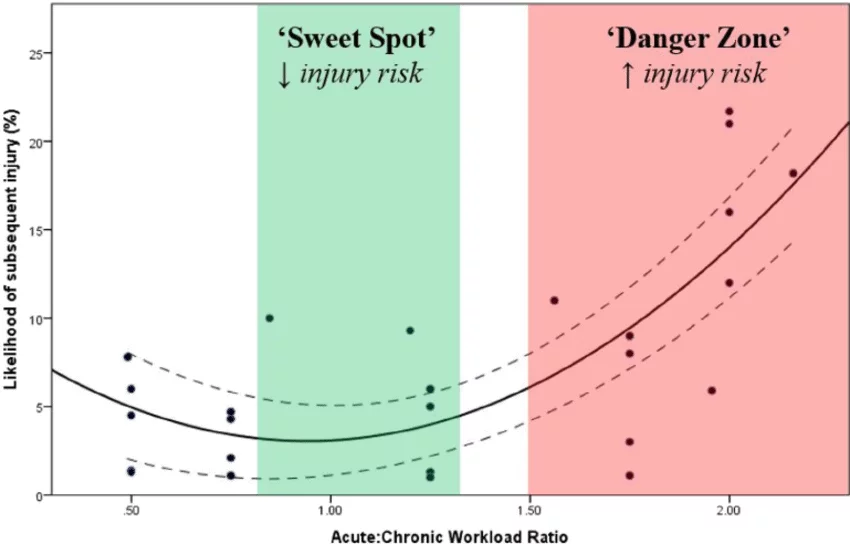

The trap is forgetting that numbers are ranges, not rights. Age, training age, health status, and injury history also are important to understand. Additionally, the work from Gabbett’s acute:chronic workload ratio still governs availability. Keep the weekly load in a stable band (~0.8–1.3) and avoid volume spikes ≥1.5 (2016, Gabbett).

Implementation That Respects Biology

Offseason: Build, Buffer, Bridge

- Build with larger accumulation blocks: aerobic capacity and general strength for structural adaptations.

- Buffer with smaller doses to maintain power and speed.

- Bridge to preseason with exposure to the highest velocities and the most specific tactical demands while tapering overall training volume.

The logic is sequenced stress, not maximal stress. Consolidate high-stress elements on the same day; place real low days in between. Respect the refractory windows of tissue and nervous system (2024, Gabbett & Oetter).

In-Season: Maintain What You Built

In-season training programs continue to be a challenge given the ever increasing number of competitions. Here are some general guidelines to help get through the in-season phase.

- Speed: one to two brief exposures weekly (≤10 s reps, full rest), even during travel weeks.

- Power: a microdose every 7–10 days—ballistics, med-ball throws, short-contact jumps.

- Strength: heavy clusters or partials every 10–14 days to keep neural drive up with low fatigue.

- Aerobic: depending on the sport, this may not need to be addressed because the sport will take care of this. If anything, longer duration Zone 2 bike rides (heart rate 60 – 70% heart rate) are probably what is missing.

Rehab: Tissue First, System Second

In rehabilitation, tissue healing sets the boundaries and Residual Training Effects help determine what can be preserved inside those boundaries.

- Bone injuries: high-impact or max-velocity activities are delayed until healing occurs, but aerobic capacity and general strength can be maintained with cycling, upper-body circuits, or blood flow restriction (BFR).

- Tendon injuries: eccentric and high mechanical stress loading is essential but must be progressed proficiently to avoid aggravation. Residuals allow you to maintain aerobic fitness and maximal strength through alternative modes while slowly progressing tendon-specific stress.

- Joint irritability: heavy compressive or rotational loads may be off-limits, but systemic qualities—such as aerobic conditioning or contralateral strength—can be trained around the joint.

RTE provides the framework for minimum effective frequency: aerobic and strength qualities can be refreshed every 10–14 days, while speed and power require earlier reintroduction once tissue tolerance allows (2024, Gabbett & Oetter).

A Case Study: The In-Season Scenario

Here is the scenario: two games per week (Tuesday and Friday), midweek travel and hotel gyms. The athlete’s strength base is solid from offseason. Their aerobic floor is fine. Game data and recent training schedule shows a lack of exposure to high speed running. That is the focus – provide a sprint stimulus.

Monday (G-1)

A speed primer: 5 × full court sprint at max effort, complete rest between reps. Then 2 sets of of low-volume med-ball rotational throws with maximal effort. Finish with posterior-chain overcoming isometrics. You’ve just refreshed the shortest residuals without creating downstream soreness.

Tuesday (Game)

Let the game deliver the glycolytic, emotional, and neuromuscular load. Don’t chase conditioning on game day; protect availability. Focus on nutrition and recovery after the game.

Wednesday (G+1, travel)

A true low day: circulation work, mobility, time off feet. Respect that tendon and the nervous system windows need time to recover following a game.

Thursday (G-1)

Power microdose + heavy clusters: trap-bar jumps 3×2 (light, snappy); bench clusters 2×5 with generous rest; Isometric adductor holds. You’ve now touched power (15±5 days) and strength (30±5 days) without tipping fatigue.

Friday (Game)

Let the game deliver the glycolytic and neuromuscular load. Don’t chase conditioning on game day; protect availability. Focus on nutrition and recovery after the game.

Saturday (G+1)

A small aerobic dose—30 minutes of extensive bike or pool (30±5 days) targeting that Zone 2 heart rate zone to promote recovery and circulation.

Sunday

Off or optional mobility. Get a massage, sauna, or cold plunge to support recovery.

Conclusion: Five Things to Remember

- Stress is a lever. The right dose at the right time keeps what matters—and leaves what can wait (1950, Selye).

- Residuals are clocks. Shorter residuals (speed/PCr) demand frequent doses; longer residuals (strength/aerobic) require infrequent doses (2016, Issurin).

- Sequencing over mixing stressors. Program compatible systems together; let residuals guide when maintenance sessions are needed (2016, Issurin).

- Fitness protects if you avoid spikes. High chronic load with stable week-to-week change reduces injury risk (2016, Gabbett).

- Tissues and CNS recover on different timelines. Build schedules with true highs and lows (2024, Gabbett & Oetter).

Free Download

Read More Like This

Related Podcasts

References

Issurin VB. Benefits and limitations of block periodized training approaches to athletes’ preparation: a review. Sports Med. 2016. (2016, Issurin).

Gabbett TJ. The training–injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:273–280. (2016, Gabbett).

Gabbett TJ, Oetter E. From Tissue to System: What Constitutes an Appropriate Response to Loading? Sports Med. 2024. (2024, Gabbett & Oetter).

Selye H. Stress and the General Adaptation Syndrome. Br Med J. 1950. (1950, Selye).