Approximate Read Time: 10 minutes

“Block periodization is about sequencing adaptations—building one quality at a time to reach peak performance when it matters most.”

What You will learn

- What block periodization is and how it works.

- Key similarities and differences with other models.

- Research evidence supporting block approaches.

What Is Block Periodization?

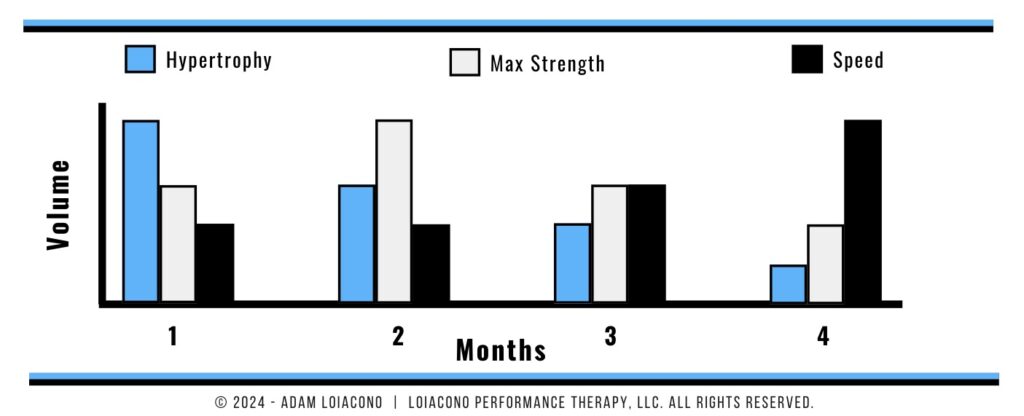

Block periodization is a structured training model that organizes performance development and rehab plans into sequential blocks, each dedicated to a specific physical quality—like hypertrophy, maximal strength, or speed. Instead of spreading multiple goals thinly across a training cycle, block periodization concentrates on one primary adaptation at a time before progressing to the next.

The design is progressive. A hypertrophy block builds the base, a strength block layers stability and force output, and a speed or power block sharpens performance. Each stage primes the athlete for the demands of the next, creating a stepwise path toward peak readiness.

This model grew out of Eastern European sports science in the mid-20th century. Soviet coaches laid the groundwork for periodization, but it was Vladimir Issurin who refined and popularized block periodization as a solution to the limitations of traditional approaches. Issurin emphasized the concept of highly concentrated workloads to maximize adaptation in each targeted attribute (Issurin, 2016).

“Block periodization is adaptation by design—each phase prepares the athlete for the next.”

Advantages and Limitations of Block Periodization

Advantages

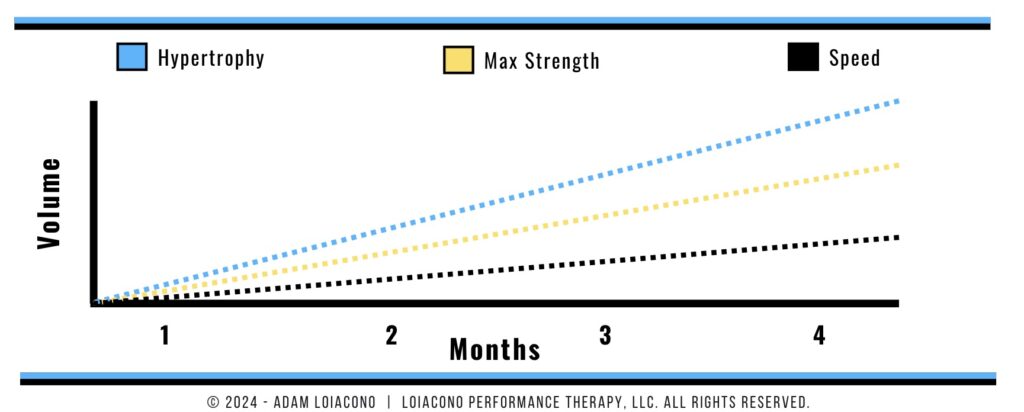

The biggest advantage of block periodization is its targeted focus. By isolating one quality per block—such as hypertrophy, strength, or power—athletes can adapt more fully to the concentrated stimulus. Issurin (2016) described this as the superiority of specialized workloads over traditional “mixed” programs that train many qualities at once but fail to develop any of them optimally.

Block structures also provide a clear, sequential pathway. For coaches and physical therapists, this means it’s easier to track progress, adjust variables, and align training stages with competition calendars. Another benefit is reduced interference between competing qualities. For example, trying to build both endurance and strength simultaneously often results in compromised gains. Separating them into blocks minimizes this conflict.

“Block training reduces the noise—one adaptation at a time.”

Finally, the structured sequencing allows for planned recovery phases, helping athletes absorb the stress of one block before tackling the next. This can lower the risk of overtraining or rehab setbacks while creating predictable performance peaks.

Limitations

Block periodization is not without drawbacks. The most obvious is the potential for detraining. When one quality is emphasized, others may regress if they’re not maintained. Issurin (2016) noted that endurance may decline during strength blocks, or maximal force capacity may fade during prolonged aerobic phases. The use of Residual Training Effects is how coaches and physical therapists could potentially minimize the detraining effect. By applying a stimulus within the frequency of a particular training quality we may be able to maintain that quality and reduce detraining.

| System/Quality | Residual Effect (days) |

| Aerobic Energy System | 30 ± 5 |

| Strength | 30 ± 5 |

| Anaerobic Energy System | 18 ± 4 |

| Power | 15 ± 5 |

| Creatine-Phosphate System | 5 ± 3 |

| Speed | 5 ± 3 |

Another limitation is rigidity. Block structures work well when an athlete has a clear, uninterrupted offseason, but they may be less practical for sports with unpredictable schedules or in-season demands. Injuries, travel, or sudden shifts in competition timing can disrupt the sequence and reduce effectiveness.

Block models can also require longer timelines. Comprehensive development may take multiple mesocycles, which is not always realistic for athletes with short offseasons or rehab windows.

Evidence From Research

Several studies have reinforced both the benefits and caveats of block periodization:

- Issurin’s Review: Issurin (2016) emphasized that block periodization provides superior adaptation compared to concurrent mixed models, especially in high-performance settings. He distinguishes between unidirectional blocks (best for single qualities like jumping) and multi-targeted blocks (suited for complex sports).

- Bartolomei et al. (2014): In trained athletes, a 15-week block program led to greater improvements in upper-body power compared to traditional linear models, even when total training volume was equated.

- Painter et al. (2012): Division I track and field athletes using block training achieved similar or better strength gains with 35% less training volume than daily undulating programs. This shows block training may be more efficient, producing greater results per unit of work.

Together, these findings highlight why block periodization is a respected model: it’s not universally better, but when matched to the athlete and context, it can be highly effective.

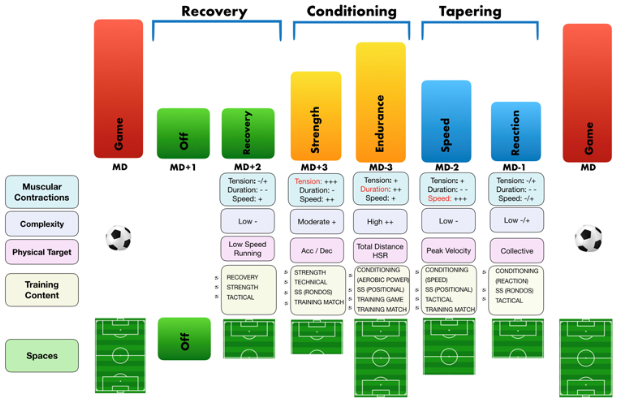

It is important to note that block periodization has shown to be effective with single event sports or offseason time windows for team sport athletes. The common denominator here is that competitions are limited and predictable. The modern athlete – professional, college, and even high school – play high volume games that can make block periodization a challenge during the season. This challenge has given rise to other periodization models such as conjugate, microdosing, and undulating models.

Comparing Block Periodization With Other Models

Block periodization is not the only way to organize training. To appreciate its role in performance and rehab, it helps to compare it directly to other popular models: linear, undulating, and tactical periodization.

Linear Periodization

Linear periodization follows a gradual, predictable progression—volume and intensity start low, then over weeks shifts toward higher intensity and volume. It works well for building foundational strength or in early rehab when predictable loading is needed.

The drawback is its predictability. Athletes often plateau because the body adapts to the steady increase in load. Compared with block, linear models lack the concentrated stress needed to maximize adaptation (Issurin, 2016).

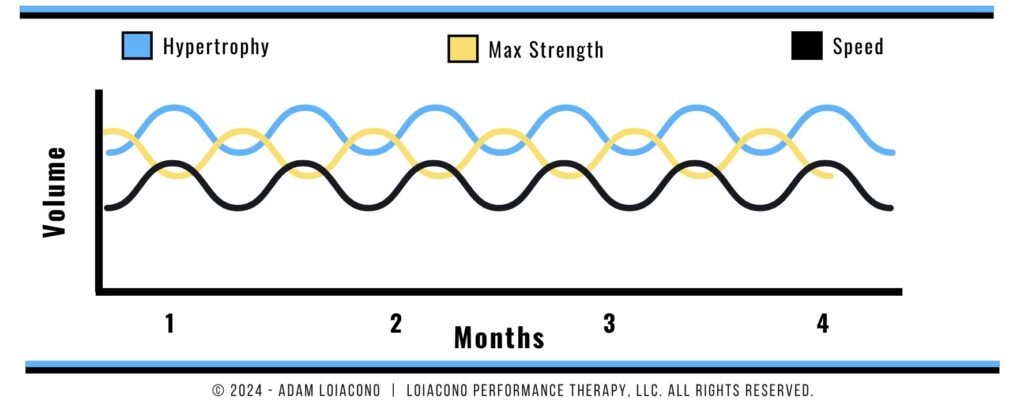

Undulating Periodization

Undulating (or nonlinear) models vary intensity and volume more frequently, sometimes daily. This prevents stagnation, keeps training fresh, and addresses multiple qualities in a shorter time frame.

However, frequent shifts can create conflicting adaptations, particularly if strength and endurance are trained side-by-side. Research shows block periodization may provide more efficient strength gains in trained populations by avoiding this overlap (Painter et al., 2012). Bartolomei et al. (2014) similarly found block training improved upper-body power more effectively than traditional or undulating approaches.

Tactical Periodization

Tactical periodization blends physical preparation with sport-specific skills, strategy, and decision-making. It’s highly effective in late-stage rehab or in-season training, when athletes must condition under game-like conditions.

But it lacks the structured isolation of block training. Tactical models rarely allow athletes to focus deeply on a single adaptation. Block’s advantage is in creating specific, sequenced peaks, while tactical training prioritizes integrated readiness.

Where Block Periodization Stands

Block periodization sits between these models:

- More structured than undulating.

- More specific and concentrated than linear.

- Less integrated than tactical, but more precise for targeted qualities.

“Block periodization isn’t better or worse—it’s different. The key is matching the model to the athlete’s needs and season.”

In other words, block training is best when athletes or rehab patients need focused progression in specific qualities—with each block deliberately setting the stage for the next.

Application in Rehab and Performance

Block periodization isn’t just for elite athletes preparing for the Olympics. Its principles translate directly to rehab and return-to-play.

Take an ACL reconstruction, for example. A hypertrophy block can restore lost muscle mass, a strength block can rebuild joint stability, and a speed or power block can prepare the athlete for cutting, sprinting, and game scenarios. Each stage flows into the next, with a logical structure that mirrors the physiological recovery timeline.

“Block periodization gives rehab structure—each phase builds logically toward return to play.”

One challenge in block models is the risk of detraining qualities not emphasized in the current block. Issurin (2016) emphasized the importance of residual training effects—the idea that certain qualities last longer than others once developed. For example, maximal strength may last longer than aerobic endurance. Understanding these timelines allows therapists and coaches to maintain “just enough” exposure to non-targeted qualities while still prioritizing the current block focus.

Block periodization’s systematic approach is what makes it attractive for rehab: it allows therapists to scale intensity, sequence adaptations, and reduce noise in a way that aligns with both healing and performance.

Key Takeaways on Block Periodization

- Block periodization = sequential adaptations. Focus on one quality at a time for concentrated gains.

- Structured progression. Each block builds on the last, creating logical steps toward peak performance.

- Reduced interference. Separating qualities avoids conflicting adaptations common in mixed programs.

- Residual effects matter. Qualities fade at different rates; smart planning keeps all systems online.

- Not one-size-fits-all. Block works best in structured off-seasons or rehab, less so in chaotic in-season play.

Free Download

Read More Like This

Related Podcasts

References

Issurin, V. B. (2016). Benefits and limitations of block periodized training approaches to athletes’ preparation: A review. Sports Medicine, 46(3), 329–338.

Bartolomei, S., Hoffman, J. R., Merni, F., & Stout, J. R. (2014). A comparison of traditional and block periodized strength training programs in trained athletes. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(4), 990–997.

Painter, K. B., Haff, G. G., Ramsey, M. W., McBride, J. M., Triplett, T. N., Sands, W. A., Lamont, H. S., Stone, M. E., & Stone, M. H. (2012). Strength gains: Block versus daily undulating periodization weight training among track and field athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 7(2), 161–169.