Approximate Read Time: 17 minutes

“Posture isn’t a fixed position; it’s a dynamic expression of our movement habits that are dramatically influenced by jobs, sports, and training history.”

What You will learn

- The historical context of posture ideals and their evolution

- The significance of movement archetypes in assessing posture

- How functional movement patterns influence performance and injury prevention

- The role of gravity, center of mass, and center of pressure in posture and performance

- Why posture assessments should be individualized, not standardized

Introduction: The Posture Debate Reignited

In the world of physical therapy and performance training, few topics generate as much debate or confusion as posture. For decades, the concept of “perfect posture” has been viewed as a cornerstone of injury prevention, movement efficiency, and even aesthetic idealism. But as our understanding of human movement evolves, so too must our frameworks.

This article isn’t about debunking posture entirely. Rather, it’s about reframing how we understand it through a modern, functional lens.

Defining Posture and Adaptation

Posture is more than just the position of the body at rest; it’s a reflection of how the body has adapted to the demands placed upon it over time. From gravity and sport to lifestyle and occupational habits, posture tells the story of stress, compensation, and survival.

Why do basketball players tend to have long limbs relative to their torsos? Why do gymnasts display pronounced lumbar lordosis? Why do swimmers often appear kyphotic with long arms and large lats? These traits are not flaws; they are adaptations. Posture optimizes function—even if it defies textbook aesthetics.

This is why there’s no such thing as a universally “perfect” posture. Instead, posture reflects the body’s ongoing attempt to solve the problems it’s given—efficiently and effectively.

“Posture tells a story—not of flaws, but of adaptation.”

Posture becomes the first insight into someone’s movement history. It is the surface expression of deeper layers of joint restriction, movement strategy, and neuromuscular patterning.

From a clinical standpoint, we can use posture as an entry point for building hypotheses. Forward head posture may suggest thoracic rigidity or suboccipital tightness. An anterior pelvic tilt may point to hip flexor dominance or poor abdominal control. Through posture, we begin to predict restrictions. Through movement and ROM testing, we confirm or deny them.

For a deeper understanding of how lifestyle influences posture and performance, explore my article on The Other 22 Hours: Rethinking Lifestyle as a Performance Variable.

The Role of Gravity and Center of Mass in Posture

Gravity is the great equalizer—it affects everyone, every day. Yet most posture assessments ignore it as a fundamental driver of compensation. Gravity pulls the body downward, and posture is the body’s strategy for resisting that pull while staying efficient and functional.

As the center of mass (COM) shifts—whether forward from prolonged sitting or laterally due to limb dominance—the body creates new patterns to maintain uprightness. These compensations become our habitual posture.

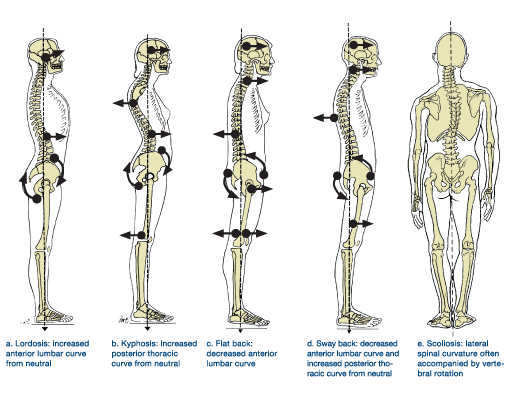

In a traditional four-posture standing screen, you can see how each progressive shift in the COM leads to further compensations:

- Mild lordosis with sacral counternutation

- Increased lordosis and kyphosis with cervical and lumbar compression

- Reversal of the pelvic tilt with sacral nutation

- Thoracic accentuation to shift weight back

Understanding how gravity influences these changes helps guide exercise prescription. COM can be manipulated to regress or progress movement. A forward COM may require posterior chain recruitment to rebalance. An anterior load during goblet squats shifts the COM backward. All of this informs our intervention.

Center of Pressure: A Window into Strategy

Complementing the concept of COM is the center of pressure (COP)—the point on the foot or hand where ground reaction forces are concentrated. Think of COP as the “output” of COM strategy. When an athlete stands or moves, COP shifts beneath their base. Where it goes tells you how they are organizing pressure and load.

In foot-based exercises:

- Heel-dominant loading pushes COP backward, encouraging posterior chain recruitment.

- Medial forefoot contact (1st MTP) shifts COP forward and medially, often tied to pronation and tibial IR.

- Lateral loading (5th MTP) biases toward external rotation and stiffness.

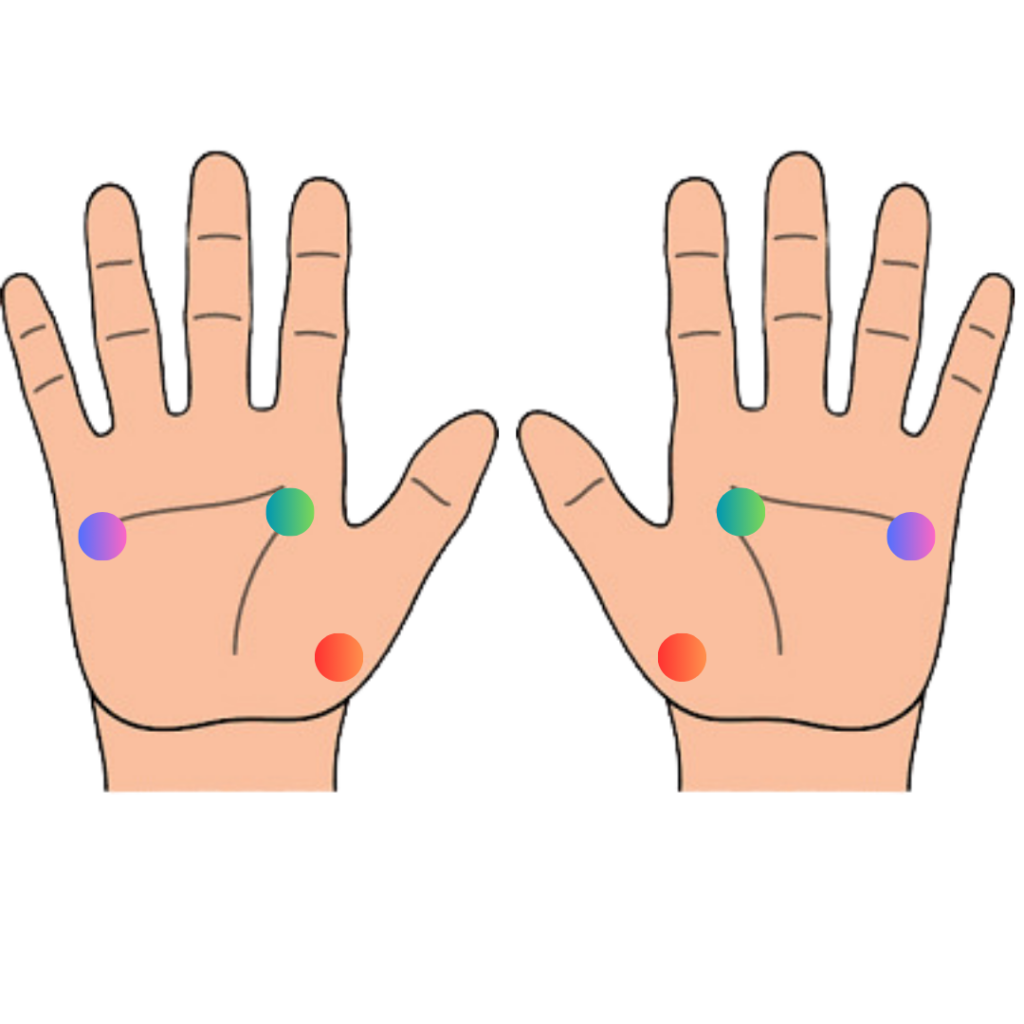

In hand-based work:

- Thenar eminence contact promotes triceps engagement and pronation.

- Hypothenar or lateral wrist loading may indicate compensatory ER or scapular elevation.

These small details—where pressure is placed on the ground—reveal movement strategies and can be directly manipulated to correct or refine motor output. If an athlete consistently overloads their lateral forefoot, chances are their COM is drifting laterally, often upstream from hip ER or downstream from ankle inversion.

“Posture is how you distribute load in space. COM and COP are how we measure that distribution.”

For insights into how barefoot training influences foot mechanics and posture, check out my article on How Barefoot Training and Footwear Shape the Way We Move.

Shirley Sahrmann and Postural Archetypes

While posture is dynamic and individualized, clinical frameworks can still help organize thinking. Shirley Sahrmann’s Movement System Impairment (MSI) model offers one of the most accessible and widely used systems. It categorizes postural faults into archetypes—such as lumbar extension syndrome, scapular downward rotation syndrome, and anterior pelvic tilt—providing a structured way to relate habitual movement to mechanical overload.

Sahrmann’s approach, though simplified, aligns with research like Torres-Tamayo’s on postural evolution and thoraco-pelvic integration. It highlights how adaptations become archetypes: repeat a compensatory strategy long enough, and it becomes your default. This is especially common in athletes with sport-specific demands.

Her model serves as a great primer, but it’s important to also understand its limitations. More complex systems like PRI, DNS, and UHP offer nuanced views of asymmetry, respiration, and segmental control. But Sahrmann’s system remains valuable as a starting lens.

“Habitual movement creates postural archetypes. Archetypes create load patterns. Load patterns create dysfunction—unless addressed.”

Fascial Chains and Postural Models: The Influence of PRI and Anatomy Trains

To deepen our understanding of posture as a dynamic system, we must look beyond bones and joints and consider the body’s fascial and neuromuscular networks. This is where models like the Postural Restoration Institute (PRI) and Anatomy Trains offer critical insights.

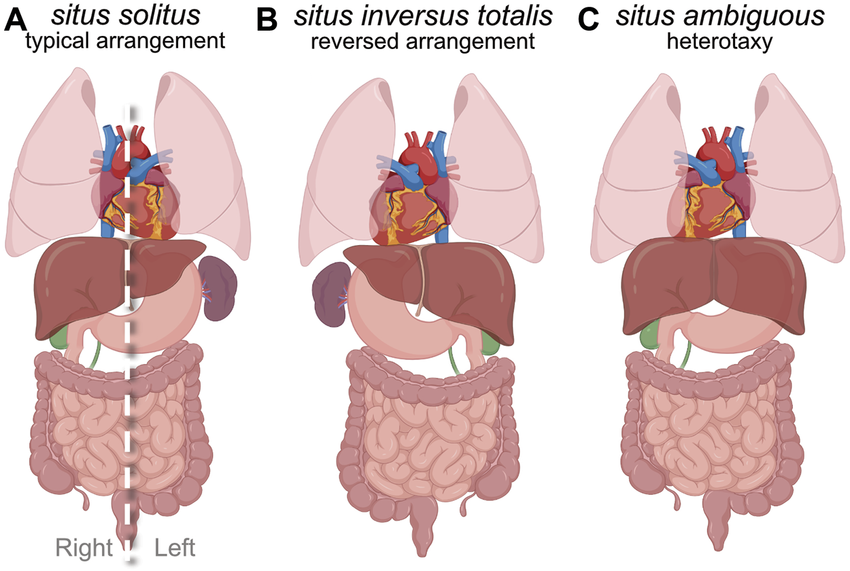

The PRI model emphasizes inherent asymmetries in the human body—particularly the dominance of the right diaphragm and the left AIC (anterior interior chain). These patterns are not dysfunctional by default; rather, they are natural biases that can become problematic when they become too rigid or unopposed.

For instance, a right-handed athlete may overuse the right posterior chain, causing rib flare on the left, anterior pelvic rotation on the right, and a tendency toward right stance bias. PRI offers specific repositioning strategies—often using the left hamstring, right glute, and respiratory coordination—to restore alternating patterns and integrated function.

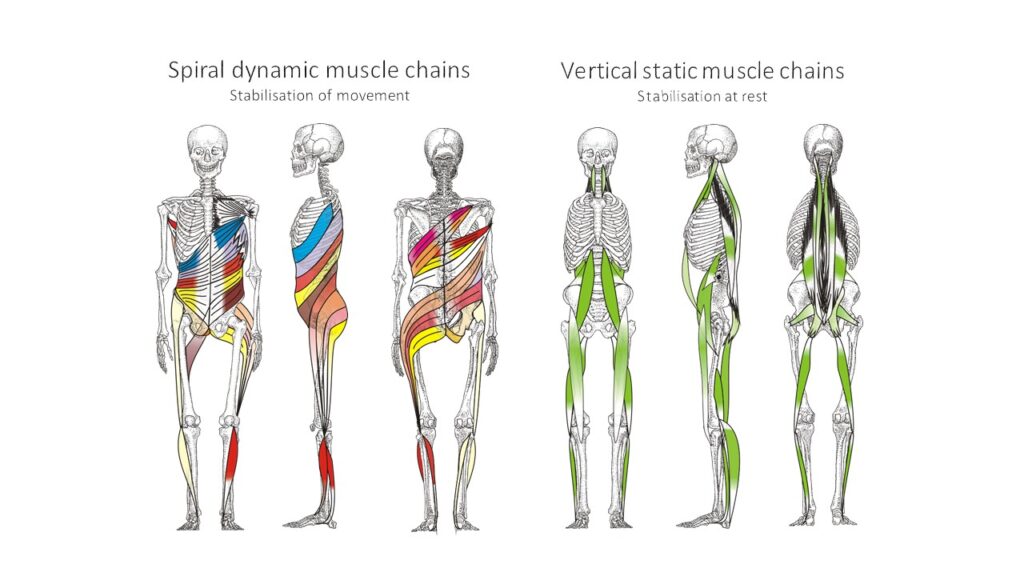

Tom Myers’ Anatomy Trains complements this perspective by mapping fascial continuity across the body through lines and spirals. These lines—like the Superficial Back Line, Deep Front Line, and Spiral Line—transmit force, store elastic energy, and organize postural tone.

When athletes lose access to one of these lines, movement compensation occurs elsewhere. For example:

- A restriction in the Spiral Line can show up as rotational asymmetries during gait or throwing.

- Inhibition along the Deep Front Line—particularly the diaphragm, psoas, or pelvic floor—can affect breathing patterns, trunk control, and even postural orientation.

Both PRI and Anatomy Trains view posture not as a static alignment, but as an emergent strategy—a reflection of how the body balances asymmetry, breath, and tension to maintain movement and uprightness. These models challenge the rigidity of traditional posture dogma by offering a fluid, systems-based view.

“Integrating concepts from Fascial Trains and PRI provides a holistic view of posture and movement.”

Four Types of Torsos: A Closer Look at Evolution

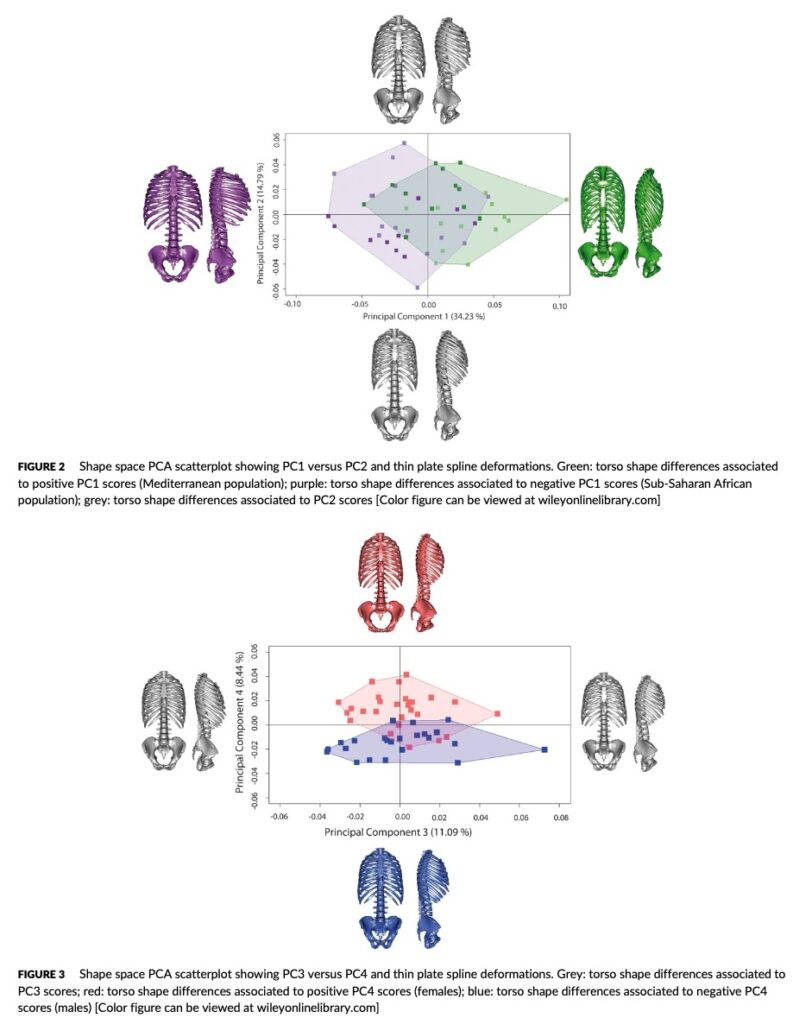

In their 2018 study, Torres-Tamayo and colleagues revisited the torso integration hypothesis and identified four distinct torso morphotypes by evaluating thoracic and pelvic shapes across modern human populations. These torso types reveal how sexual dimorphism, ancestry, and body size intersect to create meaningful differences in human shape and function. Rather than treating all torsos as functionally equivalent, the researchers proposed a more nuanced model:

- Narrow Thorax + Narrow Pelvis (Typically Male Presentation)

- Found most commonly in males, particularly in Sub-Saharan African populations.

- Associated with high thoracic depth and narrower bi-iliac breadth.

- Suited for activities that favor compactness and efficient heat dissipation (e.g., endurance sports).

- Wide Thorax + Narrow Pelvis

- A less common morphotype but one that might emerge in certain high-performance populations.

- This presentation may support increased respiratory function while maintaining mechanical efficiency in locomotion.

- Narrow Thorax + Wide Pelvis (Typically Female Presentation)

- Frequently observed in females, especially during peak reproductive years.

- Reflects adaptations to obstetric demands, increasing space for childbirth without significantly compromising thoracic capacity.

- May create challenges in maintaining spinal alignment or hip mobility if asymmetries are exaggerated.

- Wide Thorax + Wide Pelvis

- Found in larger-bodied individuals or populations adapted to colder climates.

- Offers structural robustness and increased internal volume for respiratory or metabolic capacity.

- Often presents with greater potential for force production but may limit rotational efficiency.

These four morphotypes demonstrate that posture, alignment, and movement cannot be separated from evolutionary biology or individual anthropometry. Instead of forcing everyone into a normative alignment, understanding where someone falls within these four archetypes can help refine how we assess, program, and intervene.

This framework also validates why two athletes performing the same sport may require completely different training inputs, postural expectations, or recovery strategies.

“The torso is not just a passive structure—it’s a reflection of ancestry, sex, function, and adaptation.”

Posture as a Dynamic Ecosystem

Imagine posture not as a rigid blueprint, but as a living ecosystem—constantly shaped by gravity, adaptation, skeletal architecture, neuromuscular patterns, and functional demands. Just as a tree bends with the wind, grows toward the light, and expands its roots in response to soil, the human body adapts to its internal and external environment.

Trying to define posture through static measurements alone is like evaluating a tree based solely on how upright it stands. What we miss are the forces that shape it—the slope of the hill it grows on, the direction of the sun, the pressure of the wind. Likewise, our posture is molded by the vector of gravity, the orientation of our center of mass, the way we walk, train, breathe, and recover.

Skeletal archetypes give us the framework (the soil). PRI and Anatomy Trains describe the flow of energy and force through the system (the roots and branches). Gravity and center of mass dictate how that system organizes under load (the weather patterns). And morphotypes, like those described by Torres-Tamayo, show how evolution and individual variation further diversify what “healthy” can look like.

This integrated perspective doesn’t just make us better clinicians—it makes us more precise. We stop chasing symmetry for its own sake and begin designing interventions that reflect the athlete in front of us. Posture becomes a language—a map of where the athlete has been, how they’ve compensated, and where we can go together.

“Posture isn’t a problem to be fixed. It’s a pattern to be understood.”

Final Thought

The myth of perfect posture may never fully disappear. It’s deeply ingrained in our cultural and clinical psyche. But if we’re serious about helping people move better, feel better, and perform better—we must let go of ideals and embrace individualism.

Posture is not the problem. It tells a story. And if we look closely, it will tell us exactly what the body needs.