Approximate Read Time: 20 minutes

“The scariest part of low back pain isn’t the pain—it’s not knowing what movements are safe anymore.”

What You will learn

- Discogenic low back pain is increasingly prevalent in young athletes.

- MRI often reveals disc desiccation or protrusion, even without nerve involvement.

- Mechanical load and center of mass (COM) awareness are key to managing disc stress.

- Flexion vs. extension bias in rehab should be guided by disc morphology and symptoms.

- Progressive return to running should consider decompression, lumbopelvic control, and ground contact time progression.

When Low Back Pain Hits Before Adulthood

Low back pain is no longer just an adult problem. Today’s youth athletes face earlier specialization, higher training volumes, and limited downtime—all contributors to mechanical overload of the spine. While the term “disc injury” often sparks fear in both athletes and parents, the presence of a disc protrusion or desiccation on MRI doesn’t always require a surgical solution. More often, it demands a smarter, system-wide response.

In this article, we’ll unpack the mechanisms behind discogenic low back pain, clarify when disc issues matter, and outline a progressive strategy rooted in decompression, motor control, and gradual reloading.

Understanding Lumbar Disc Pathomechanics

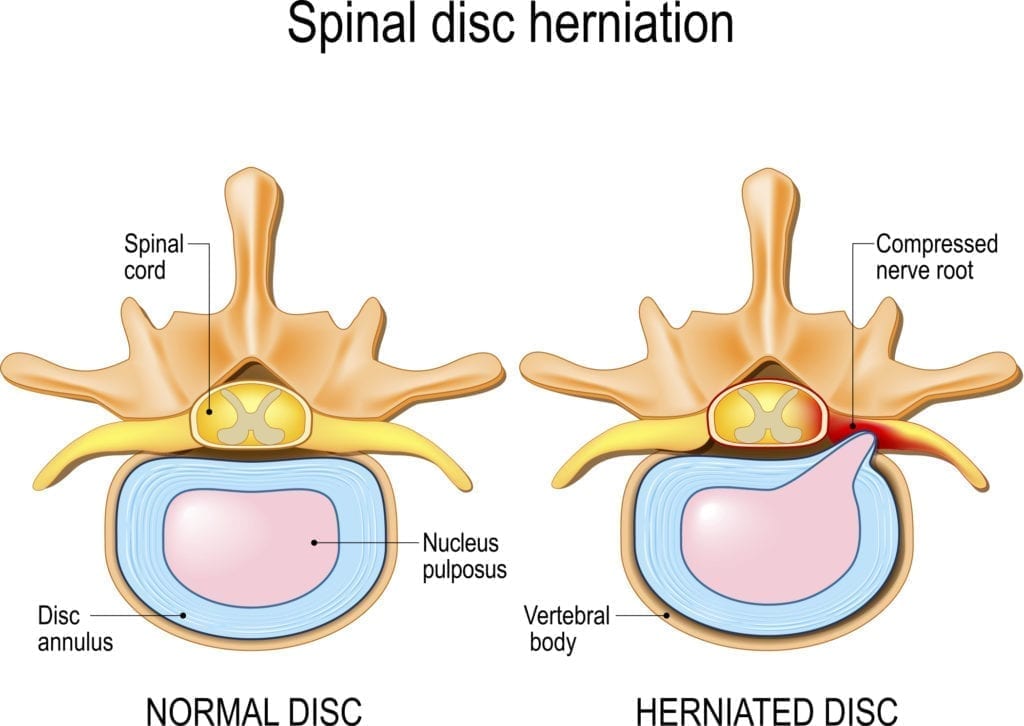

The intervertebral disc acts as a shock absorber between vertebral bodies. It’s composed of a gelatinous nucleus pulposus surrounded by a fibrous annulus fibrosus. With chronic stress, poor movement patterns, or high loading, the nucleus can migrate and create disc protrusions.

Often times I hear a patient or athlete say their doctor recently told them they have a disc protrusion and that is what is causing their back pain. Maybe, maybe not. Consider this:

Studies using MRI in asymptomatic individuals report a prevalence of 30% in general populations, with higher rates (up to 76%) in groups matched for age, sex, and occupational risk factors. Most herniations are mild (bulges or protrusions), and the prevalence increases with age.

Anterior vs. Posterior Disc Protrusions

- Posterior disc protrusions are far more common. These occur when flexion and axial load cause the nucleus to push backward, often irritating nearby nerves or creating central pressure.

- Anterior protrusions are rare but can result from chronic hyperextension and anterior shear. While less clinically significant, they highlight the importance of spinal alignment in both flexion and extension.

“Disc herniation is often less about the disc—and more about the direction of pressure.”

When symptomatic, protrusions can create local pain, stiffness, or referral patterns depending on direction and severity. However, many athletes have asymptomatic disc findings, which means imaging must always be interpreted through the lens of movement and presentation.

How Flexion & Extension Bias Can Guide Rehab

Flexion and extension based exercises have different impacts on the mobility of the disc. Flex causes the nucleus pulposus (the disc’s inner gel) to migrate posteriorly, increasing pressure on the back (posterior) part of the disc. This can worsen or provoke posterior disc protrusions, which are the most common type and often cause nerve compression and pain.

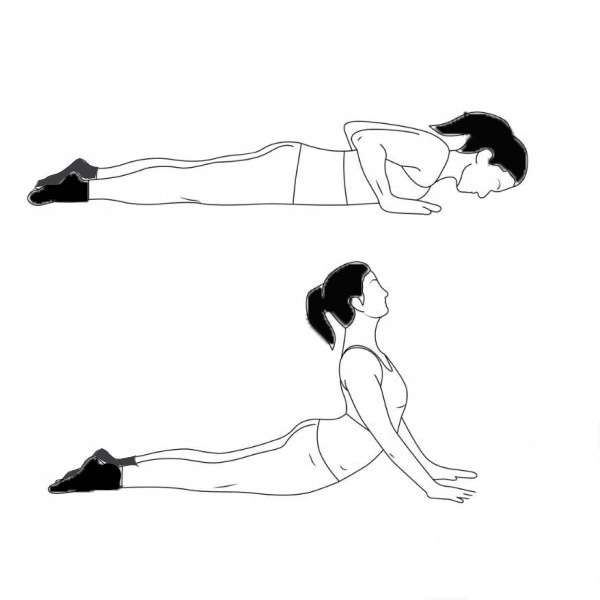

Extension exercises moves the nucleus pulposus anteriorly, reducing pressure on the posterior disc and potentially relieving symptoms of posterior protrusions. Extension can also increase compressive stress in the posterior annulus in some cases, but often provides relief for posterior herniations.

In a more practical sense within the stages of the injury and symptoms, here is how we leverage flexion and extension exercises:

- In posterior disc protrusions, controlled extension work (e.g., prone press-ups, cobra progressions) can help centralize symptoms and promote anterior migration of the nucleus.

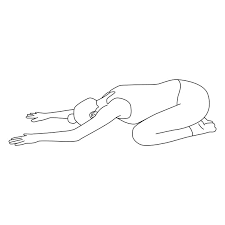

- In acute stages or with high irritability, neutral or flexion-bias positions like hook-lying breathing drills, sidelying 90/90, and supported glute bridges can reduce spinal compression and allow the system to decompress.

The Importance of Center of Mass in Early Low Back Pain Rehab

“Managing center of mass is the foundation of managing discogenic pain.”

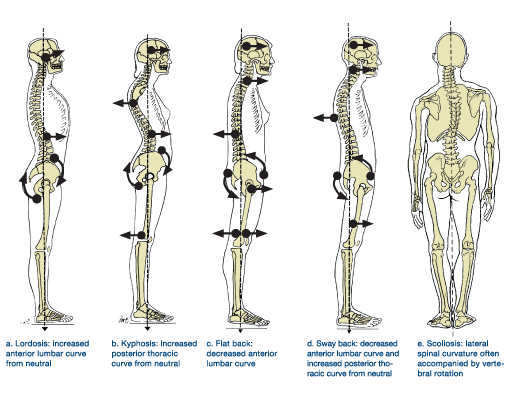

Early-phase rehab isn’t just about which exercises to select—it’s about how the athlete experiences and distributes load. A common mistake is loading athletes in positions where their center of mass drifts outside their base of support.

This shift will change how gravity impacts the entire skeleton. When the center of mass shifts, so do joint positions:

Preparing the Athlete: Movement Foundations

True recovery goes beyond isolated core work. Movement preparation should include three core domains:

1. Lumbar Decompression

- Sidelying and hook-lying drills with balloon-based or resisted breathing

- Supine dead bugs and glute bridges for spinal unloading

- Hanging or long-axis distraction under supervision

2. Lumbopelvic Control

- Split stance isometrics

- Hinge variations from tall kneeling → KB DL → SLDL

- Anti-extension work: dead bugs, stir-the-pot, half-kneeling lifts

3. Graded Exposure to Running & Plyometrics

- Marching drills with wall support → sled push variations

- Progression based on ground contact time (GCT): longer → shorter → explosive

- Use A-skips, single leg hops, and resisted sprints to bridge back to sport

“The rehab plan should flow like athletic development: stable → dynamic → reactive.”

Final Thoughts: Reframing the “Disc Problem”

“Disc pain isn’t an endpoint—it’s an invitation to train smarter.”

Discogenic pain in youth athletes requires more than a diagnosis—it requires context. Pathomechanics, movement strategy, and load sequencing must guide rehab, not fear or static protocols. Using disc findings as a diagnostic cue—not a prognosis—allows physical therapists, athletes, and active adults to rebuild both movement and confidence.

Recommended Podcast

References

Varun S. et al. “PREVALENCE OF LUMBAR INTERVERTEBRAL DISC HERNIATION IN ASYMPTOMATIC INDIVIDUALS ON MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING – MULTICENTER HOSPITAL BASED STUDY.” PARIPEX INDIAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH (2025). https://doi.org/10.36106/paripex/7406589.

A. J. Fennell et al. “Migration of the Nucleus Pulposus Within the Intervertebral Disc During Flexion and Extension of the Spine.” Spine, 21 (1996): 2753–2757. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199612010-00009.