Approximate Read Time: 15 minutes

“Pain is unique to every individual and is dependent on individual past experiences, current emotions, and future goals.”

What You will learn

- Pain involves tissue damage, emotional, cognitive, and environmental factors, and understanding this complexity is crucial for effective rehabilitation.

- Pain perception varies based on the individual’s personal, emotional, and social context, highlighting the importance of framing pain within these factors in therapy.

- The brain’s “virtual body” concept explains how pain persists in conditions like phantom limb pain, necessitating therapies that target brain remapping.

- Pain is influenced by brain decision-making and hypersensitivity, meaning treatments should address nervous system retraining alongside tissue healing.

- Patient education about pain and graded exposure to movement help reduce fear, modulate the nervous system, and promote recovery.

The Contextual Nature of Pain

Pain is a normal response from the body’s alarm system, aimed at protecting and preserving us. It involves not just tissue damage but also input from emotional, cognitive, and environmental factors. In this article we will explore how crucial it is to understand that pain is multifactorial, influencing rehabilitation outcomes and treatment plans.

Pain is heavily influenced by context. It is not merely a straightforward response to tissue damage but depends on how the brain interprets sensory inputs, past experiences, beliefs, and emotional states. For example, a professional violinist might feel more pain from a minor finger injury than a non-musician because the injury affects their livelihood and identity. Understanding this helps therapists frame pain within the client’s personal, emotional, and social context

During rehabilitation, we have to be mindful of how athletes or clients perceive pain and how it affects their performance. Pain doesn’t always correlate with the severity of the injury and that managing thoughts and emotions can impact recovery outcomes.

Brain Mapping and Phantom Limb Pain

The concept of brain mapping illustrates how the brain holds a “virtual body” that persists even after physical changes occur, such as in the case of phantom limb pain. This concept is relevant for understanding chronic pain conditions where pain continues despite healed tissues or no ongoing injury. The brain’s perception, often influenced by past trauma or injury, plays a significant role in the continuation of pain.

Techniques such as graded motor imagery, visualization, or sensory retraining can help the brain remap and desensitize affected areas.

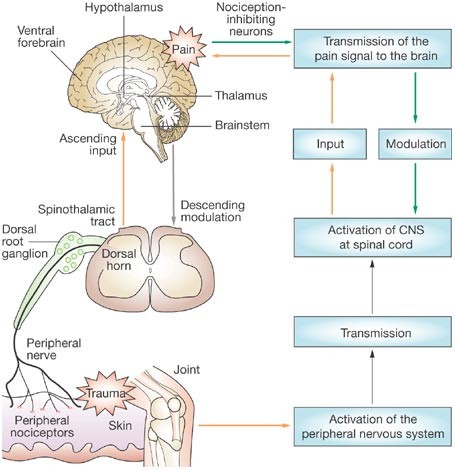

Nociception and the Brain’s Decision-Making

Nociception refers to danger signals detected by receptors in the body, which may or may not result in pain. The brain decides whether to interpret these signals as pain based on a variety of factors. This means pain isn’t always directly tied to the extent of an injury but to how the brain processes these danger signals. Central sensitization, a phenomenon where the brain becomes hypersensitive, can result in amplified pain even without a current injury.

Emotions and Pain

Emotional and psychological factors play a significant role in pain experiences. Stress, anxiety, and negative beliefs can exacerbate pain, while positive emotions and relaxation can reduce its intensity. Cognitive-behavioral approaches, combined with physical rehabilitation, are essential in reducing the impact of negative emotions on pain perception.

Integrating relaxation techniques, cognitive-behavioral approaches, and education to help clients manage their emotional response to pain. Encouraging mindfulness and positive thinking can help in down-regulating the nervous system’s sensitivity to danger signals.

The Role of the Central Nervous System in Chronic Pain

Chronic pain often stems from central sensitization, where the central nervous system (CNS) becomes overly sensitive to normal stimuli. In these cases, pain persists even after the initial tissue injury has healed. The spinal cord and brain amplify these danger signals, causing heightened sensitivity to pain and prolonged discomfort

The best way to desensitize the CNS through graded exposure, gentle movements, and progressive loading of injured tissues. This can help retrain the brain and nervous system to interpret signals more accurately, reducing pain in the long run.

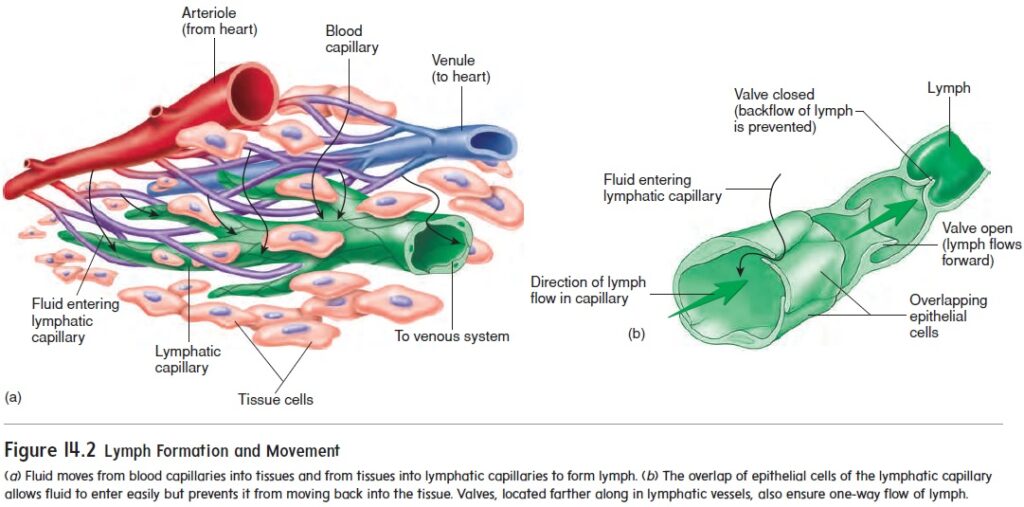

Inflammation and Movement

Inflammation plays a role in pain, especially in conditions like arthritis or post-injury recovery. The by-products of cell activity, such as acids, can build up in tissues when movement is restricted, leading to increased pain and stiffness. Movement, even in small doses, is essential to managing pain by flushing these by-products from the tissues and promoting healing.

Movement is a primary tool in pain management. Graded exposure to activity helps reduce pain by improving circulation and flexibility, especially in chronic conditions where stiffness and immobility contribute to pain.

Education as a Tool for Managing Pain

One of the key takeaways is the importance of educating patients about pain. When clients understand that pain is part of the body’s protective system and can be modulated by the brain, they are less likely to fear it. This reduction in fear encourages participation in rehabilitation activities, which are crucial for recovery

Education should be a fundamental part of every therapy session. Teaching patients about the nature of pain, how the brain contributes to their pain experience, and how they can actively participate in their recovery empowers them to take control of their healing process.

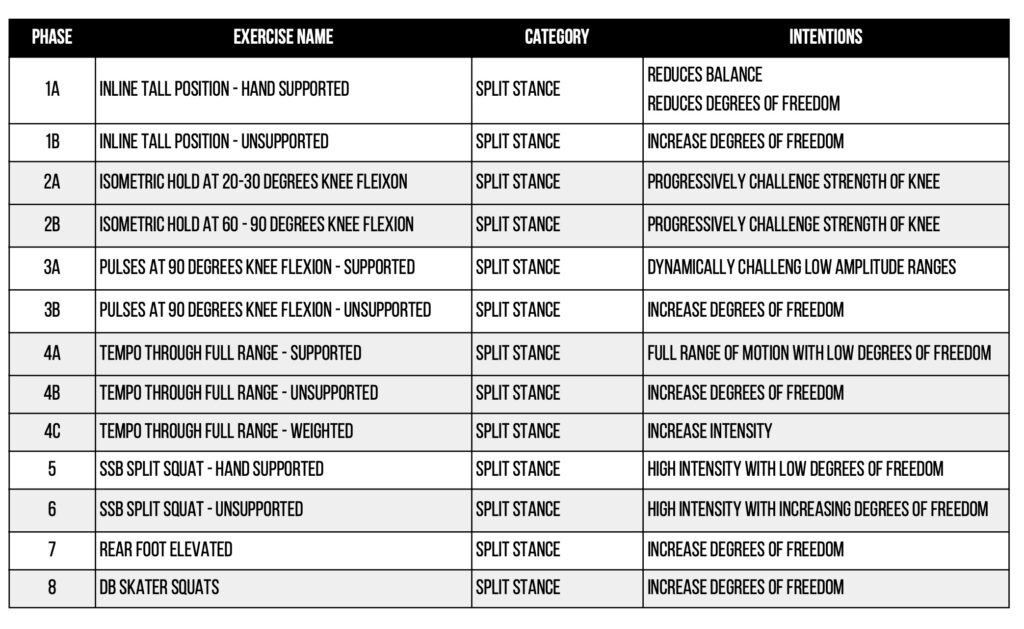

Graded Exposure and Cognitive Strategies

Graded exposure to movement and cognitive strategies, such as challenging negative beliefs about pain, are key tools in rehabilitation. Slowly increasing activity levels allows the nervous system to adapt without triggering excessive pain responses, while cognitive strategies help patients alter their perception of pain, reducing its intensity.

Incorporating graded exposure techniques by progressively increasing the difficulty of exercises and activities. Pair this with cognitive interventions to challenge negative thoughts and beliefs about pain. This dual approach helps to retrain both the mind and body, improving overall outcomes.

Conclusion

Pain science has evolved significantly, shifting from the view that pain is solely a result of tissue damage to a broader understanding of pain as a complex and multifactorial experience. Pain is not just a signal of injury but is influenced by how the brain interprets sensory inputs, context, emotions, and past experiences. Pain can persist even when tissues have healed, due to changes in how the central nervous system processes and amplifies these signals.

Understanding that pain is a protective mechanism initiated by the brain opens new pathways for treatment. Pain is shaped by factors such as stress, fear, beliefs, and emotional states, meaning that managing pain effectively requires addressing both the physical and psychological aspects of the experience. Education about how pain works can reduce the fear surrounding it, helping individuals become less threatened by their symptoms and more empowered to take control of their recovery.

Movement and graded exposure to physical activities are crucial in pain management, as they help retrain the nervous system and re-establish healthy patterns of movement. Cognitive strategies, such as reframing negative beliefs about pain, can further reduce its intensity by changing the brain’s response to perceived threats.

References

Butler DS, Moseley GL. Explain Pain. 2nd ed. Noigroup Publications; 2013.