Approximate Read Time: 13 minutes

“Healing meniscus tears isn’t about shortcuts—it’s about respecting biology, rebuilding strength, and progressing with purpose until the knee is strong enough for sport again.”

What You Will Learn

- Meniscus anatomy, blood supply, and biomechanics

- Surgery vs. non-surgical treatment outcomes

- Proven rehab phases with key benchmarks

Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Meniscus

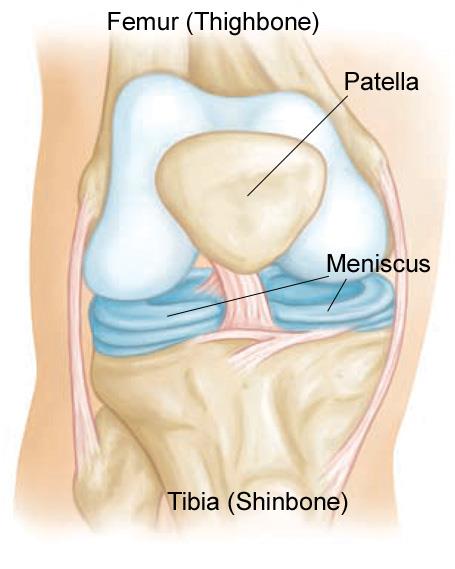

The medial and lateral menisci are fibrocartilaginous wedges that serve as the knee’s shock absorbers and stabilizers. Their crescent shape and attachments allow them to distribute load, increase joint congruency, lubricate the joint, and protect articular cartilage from overload.

The medial meniscus, bound tightly to the medial collateral ligament (MCL), is less mobile and therefore more prone to injury during valgus or rotational stresses. The lateral meniscus, more mobile, better accommodates femoral motion but can be compromised during cruciate ligament injuries.

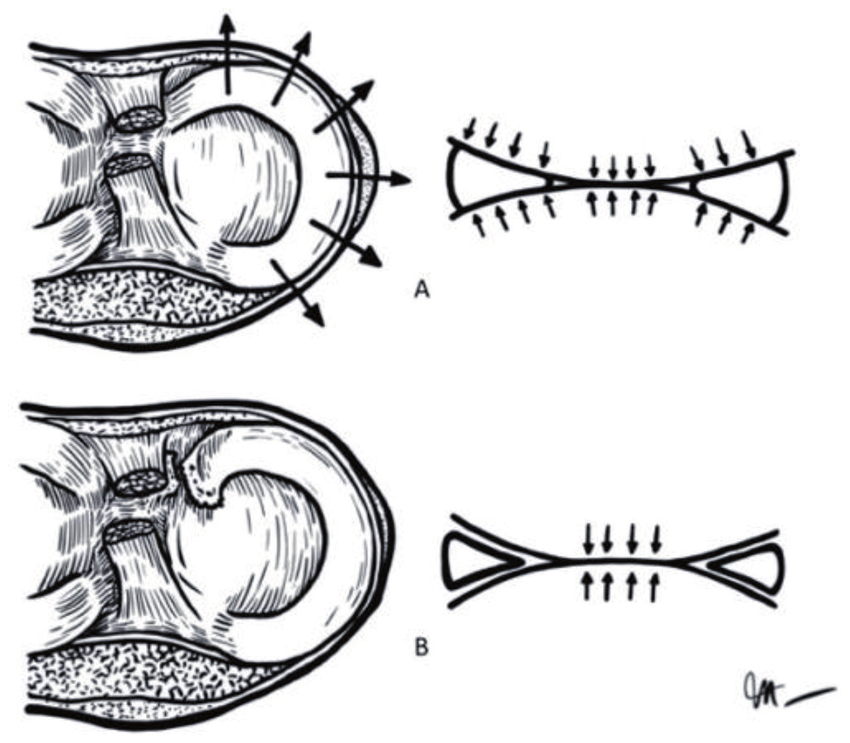

Hoop Stresses: The Meniscus as a Suspension Cable

When axial loads press into the tibiofemoral joint, the meniscus converts that vertical stress into circumferential “hoop stresses,” distributing pressure outward like the tension of a suspension bridge cable. When intact, these stresses protect the cartilage. But when a meniscus root tears, hoop stresses fail—contact pressures spike, cartilage degenerates, and arthritis accelerates.

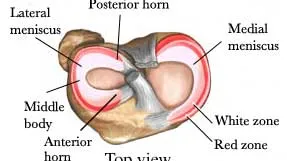

Vascular Zones

Healing potential is dictated by blood supply:

- Red-Red Zone (outer third): well-vascularized, good healing.

- Red-White Zone (middle third): partial vascularity, moderate healing.

- White-White Zone (inner third): avascular, poor healingKnowledge Base. Meniscus..

This gradient explains why some tears heal with conservative care while others struggle without surgical repair.

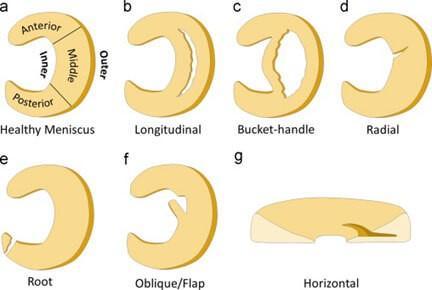

Types of Meniscus Tears

The shape and location of a tear influences both symptoms and treatment options:

- Longitudinal tears: often repairable if located peripherally.

- Radial tears: disrupt hoop stresses, harder to heal.

- Horizontal tears: typically degenerative, less repair potential.

- Bucket handle tears: displaced vertical tears, often causing mechanical locking.

- Root tears: disrupt biomechanics entirely, closely linked to early arthritis.

- Complex tears: involve multiple planes, challenging to treat.

“Not all meniscus tears are created equal—root tears behave like ruptured ligaments, while horizontal degenerative tears behave more like wrinkles in fabric.”

Surgery or Not?

For years, arthroscopic partial meniscectomy was considered routine. Today, the evidence paints a more nuanced picture.

Sham vs. Meniscectomy

The FIDELITY sham-controlled trial showed no difference in pain or function between arthroscopic partial meniscectomy and sham surgery at one year (Sihvonen, 2013). Similarly, a Cochrane review concluded that arthroscopic surgery offers little to no benefit for degenerative tears or osteoarthritis (O’Connor, 2022).

In another RCT, arthroscopic meniscectomy provided no long-term advantage over structured exercise in patients with degenerative horizontal tears (Yim, 2013).

Non-Operative vs. Meniscectomy

In a randomized control trial, Yim et al. compared arthroscopic meniscectomy to structured exercise. After 2 years, outcomes were identical. Both groups improved, but surgery offered no advantage (Yim JH, 2013).

Meniscal Root Tears: The Exception

Meniscus root tears are a different story. A systematic review found repair had the best outcomes, with conversion to total knee arthroplasty ranging from 0–1%, compared to 11–54% for partial meniscectomy and 31–35% for conservative care (Stein, 2020). A matched cohort from Mayo Clinic confirmed that repair minimized arthritis progression and prevented progression to arthroplasty compared with meniscectomy or non-operative care (Bernard, 2020).

“If degenerative tears are the gray zones, then root tears are the black and white—fix them early or face early arthritis progression.”

Swelling as the Keystone Symptom

Every meniscus rehab story revolves around swelling.

When a meniscus is injured or surgically repaired, the knee’s inflammatory response sets off a cascade designed to protect and heal. Blood vessels dilate leading to fluid in and around the joint capsule. While this reaction is biologically purposeful, unchecked swelling quickly becomes the rate limiter of recovery.

- Limits Range of Motion (ROM)

Excess joint effusion increases pressure inside the joint, making flexion and extension physically harder. Imagine trying to bend a water balloon—you can force it, but resistance rises sharply as the capsule stretches. In meniscus rehab, loss of full extension is particularly problematic, as it alters gait mechanics and creates compensatory stress on other structures. - Amplifies Pain via Nociceptor Activation

The inflammatory “soup” of cytokines, prostaglandins, and histamine excites nociceptors (pain receptors) embedded in the capsule. This doesn’t just cause pain—it heightens sensitivity. Patients report sharp pain even with simple, non-threatening movements. In effect, swelling turns up the volume of the body’s “danger alarm system” (Butler & Moseley, 2003). - Shuts Down Quadriceps through Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition (AMI)

Perhaps most insidious, swelling triggers spinal reflexes that inhibit quadriceps activation (VanderHave, 2015). This isn’t weakness from atrophy; it’s a neural “off-switch” that prevents efficient muscle contraction. Without quads, gait mechanics falter, patellofemoral stress increases, and athletes cannot achieve the strength benchmarks required for safe return.

Weight-Bearing Debate: Early vs. Delayed

Earlier literature advised restricting weight-bearing to protect healing tissue (Chiang, 2011; Haas, 2005). But biomechanical and animal studies show hoop stresses from weight-bearing may actually promote healing (VanderHave, 2015).

Recent RCTs show no difference in failure rates between restricted and accelerated protocols (Lind, 2013). Accelerated programs improve compliance and allow earlier return to activity without compromising outcomes (Mariani, 1996; Barber, 2008).

Modern consensus: early partial weight-bearing, progressing to full by 4–6 weeks, individualized by tear type and repair (VanderHave, 2015).

I favor early partial weight-bearing, but tailor the progression to the tear type and surgical repair. There are certainly cases where earlier weight-bearing is possible, and I tend to error on the side of caution following early post-operative care to best allow the meniscus to heal.

Sample Rehab Plan

In the following sections we are going to review key milestones and topics to consider within early, middle, and late rehab. This is not an exhaustive plan and it goes without saying every athlete and rehab case must be individualized.

Early Rehabilitation: Swelling, Range of Motion, Quadriceps

Time: 0 – 6 Weeks

- Quiet knee (minimal swelling, pain control, infection-free).

- Range of motion to 90°.

- Quadriceps activation.

- Full weight bearing

Tools

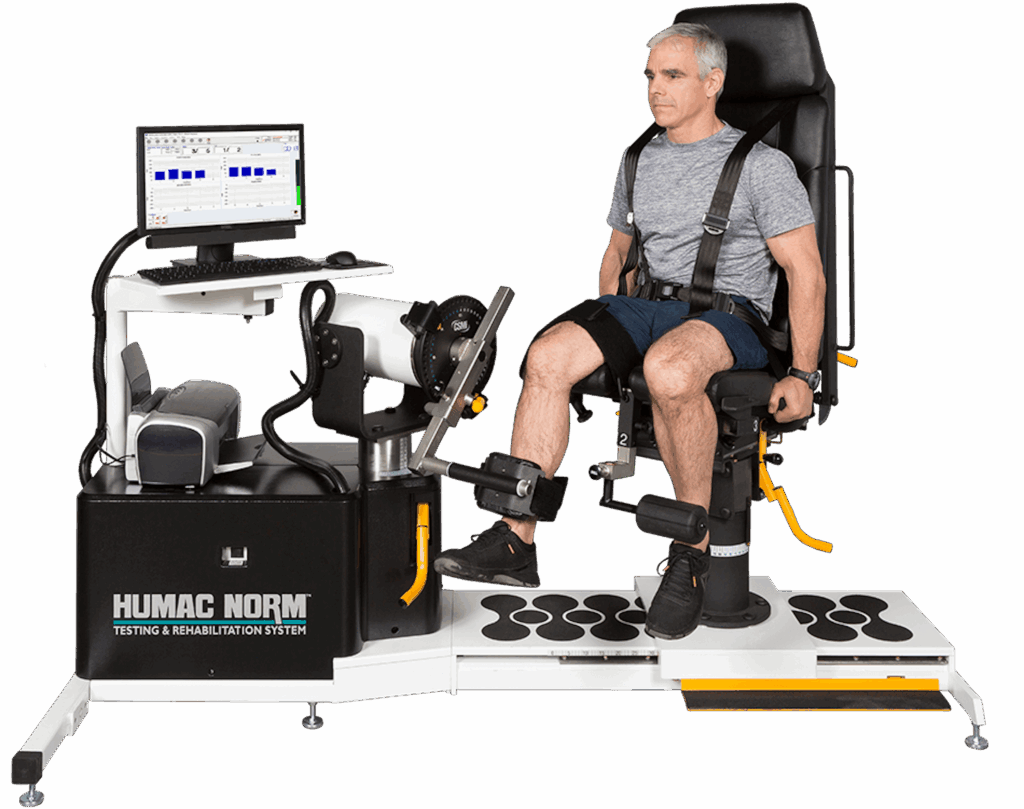

- Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation (NMES): restores quad firing despite inhibition.

- Blood Flow Restriction (BFR): promotes strength and slows atrophy with low loads.

- Pool therapy: combines buoyancy and hydrostatic pressure for safe closed-chain activity while improving circulation to reduce swelling.

Precautions

- Avoid deep flexion >90°.

- Avoid resisted hamstring activity because of the distal attachment of the hamstring into the meniscus.

Middle Rehabilitation: General Physical Preparation

Time: 6 – 14 weeks

Targets for isokinetic Tests

- Quad isometric @ 60°: 120% bodyweight

- Hamstring:Quad concentric ratio: ~70%.

- Concentric quad torque: 100% bodyweight

- Squat 3RM @ 0.3–0.4 m/s at 1.5× BW.

- Nordics: 405 N with <10% asymmetry.

This is the “base of the pyramid” phase. Athletes restore both the “parts” and the “system” by focusing on the strength and outputs. You can only build a pyramid so high depending on the size of the base. The bigger the base, the higher the pyramid.

End-Stage Rehab: Force, Power, and Deceleration

Time: 14+ weeks

The meniscus must tolerate not just strength, but the violent demands of sport—braking, cutting, and landing. Deceleration and eccentric strength are critical at assuring the knee is prepared for sport and activities.

Force Plate Benchmarks

- CMJ height: 40 cm.

- RSI-mod: 0.55.

- Eccentric braking impulse asymmetry: <10%.

- 10-hop RSI: 2.0 with asymmetry <10%.

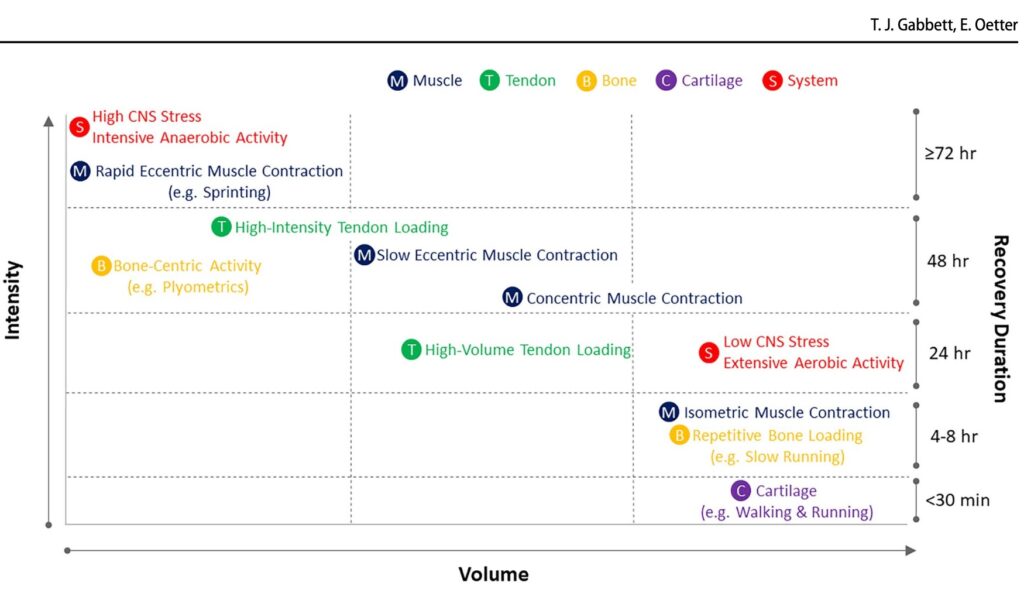

Tissue Tolerance and Healing Timelines

Biological healing follows phases and no matter how many modalities we throw at the knee, there are just some things we cannot change. Below are 3 phases of healing relative to biology and tissue types.

- 0–3 months: fragile fibrocartilage (meniscus is vulnerable)

- 3–6 months: collagen maturation (meniscus still vulnerable)

- 6–12 months: near full biomechanical strength, but remodeling may take 18 months.

The article From Tissue to System (Gabbett, 2024) stresses that tissue response guides system progression—not the other way around. In practice: swelling is a signal of load tolerance, not just setback. Swelling is a normal part of the progressions, and is our single most important key performance indicator.

Practical Roadmapping and Mistakes to Avoid

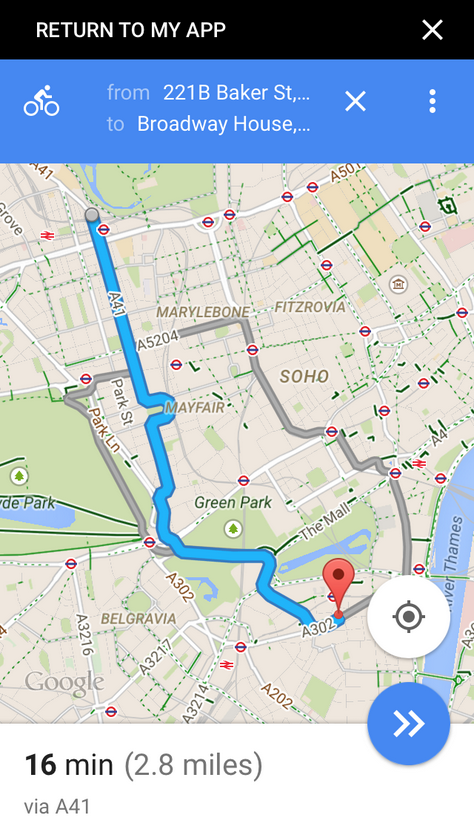

The best rehabs are not improvised, they’re engineered backwards. Just as we begin driving a car with a route to our end destination in mind, rehab should be reverse-engineered from the end goal—safe return to play at 9–12 months.

This doesn’t mean every athlete follows the same straight line. It means the map is drawn with checkpoints and possible different routes. Those checkpoints include a quiet knee, restored ROM, isokinetic symmetry, eccentric control, and sport-specific power. How quickly or slowly someone moves between those checkpoints depends on how their knee responds to stress and will guide which route may be taken.

This is where swelling, force plate testing, and performance benchmarks act as guardrails. Push too fast, swelling and asymmetries flare up. Stay too conservative, and the athlete is morally defeated. The art of meniscus rehab lives in this balancing act—knowing when to hold steady, when to accelerate, and when to pivot.

Yet even with a solid roadmap, three predictable pitfalls can derail recovery:

Three Biggest Mistakes

- Returning to impact without adequate quad strength. Without quads, the knee simply cannot tolerate the repeated braking demands of running and cutting.

- Underdeveloped eccentric control—both fast and slow. Deceleration is as important as acceleration; without it, knees collapse under the very forces sport demands.

- Neglecting swelling and quad activation, assuming they are “early-phase” issues only. Effusion and inhibition are not boxes to check in week two—they’re ongoing battles that can resurface any time load outpaces healing.

In short: Most failed rehabs are not from lack of effort, but from ignoring the biological checkpoints that dictate readiness—swelling quieted, quads firing, and the brakes fully rebuilt.

Conclusion

Meniscus rehab demands more than time on a calendar—it demands respect for anatomy, biomechanics, and biology. At the start of this guide, we outlined three essentials:

- Understand the meniscus as a load-bearing structure

- Recognize that treatment decisions depend on tear type and long-term outcomes

- Follow phased rehabilitation principles that restore range of motion, strength, and tissue tolerance

Every decision, from managing swelling to introducing force-plate testing, comes back to one idea: progress is dictated by biology, not wishful thinking.

Where most rehabs falter is not from lack of work, but from missteps we can predict: returning to impact before quadriceps are strong enough, neglecting eccentric braking capacity, and assuming swelling and quad inhibition vanish after the first few weeks.

The solutions lie in reverse-engineering the process: monitor swelling as your compass, use objective benchmarks to check the brakes as well as the engine, and layer in sport-specific exposures only when the system is ready. Done this way, the path from injury to return to play is less about surviving 9–12 months and more about building a stronger, smarter, and more resilient knee than before.

5 Keys to Meniscus Rehab

- Respect Biology – Healing timelines are non-negotiable; swelling and tissue tolerance dictate the pace.

- Protect & Restore ROM – Full extension and gradual flexion recovery set the foundation for movement quality.

- Activate & Strengthen Quads – Overcome arthrogenic muscle inhibition early and keep progressing until symmetry is restored.

- Build the Brakes (Eccentric Control) – Both slow and fast deceleration capacity are critical before impact and sport return.

- Follow Objective Checkpoints – Use swelling, isokinetic data, and force-plate metrics as your roadmap, not the calendar.

Free Download

Read More Like This

Related Podcasts

References

VanderHave KL, Perkins C, Le M. Weightbearing versus nonweightbearing after meniscus repair. Sports Health. 2015;7(5):399-403.

Gabbett T, Oetter E. From tissue to system: what constitutes an appropriate response to loading? Sports Med. 2024.

O’Connor D, Johnston RV, Brignardello-Petersen R, et al. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;3:CD014328.

Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy vs sham surgery. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2515-2524.

Yim JH, Seon JK, Song EK, et al. Comparative study of meniscectomy and nonoperative treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(7):1565-1570.

Stein JM, Yayac M, Conte EJ, Hornstein J. Treatment outcomes of meniscal root tears. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2020;2(3):e251-e261.

Bernard C, Tagliero A, LaPrade M, et al. Medial meniscus posterior root tear treatment. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(7 Suppl 6).

Guerrero JG, Foidart-Dessalle M. Kinematics of normal menisci during knee flexion. J Anat. 2003.