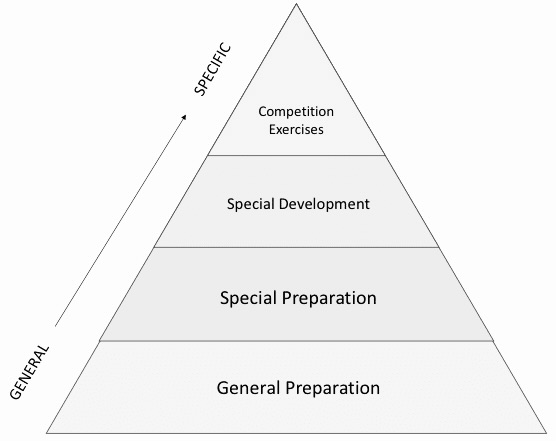

In the world of sports rehabilitation, the transition from injury recovery to peak performance requires a careful balance of general and specific training adaptations. This continuum is crucial for returning athletes to competition safely and effectively. In Episode 41 of the Finding Small Wins podcast, Joel Jamieson’s framework of general versus specific adaptations provides a structured roadmap for integrating conditioning into return-to-play protocols and general fitness. By understanding how to progress from broad fitness qualities to sport-specific readiness, we can optimize both recovery and performance.

Understanding General vs. Specific Adaptations

General Adaptations

General adaptations refer to the foundational physical qualities that are necessary across all sports or activities. These include aerobic fitness, strength, mobility, and basic motor skills. For example, aerobic fitness measured by resting heart rate or VO2 max serves as a cornerstone for recovery and readiness. Without this baseline, athletes lack the capacity to handle even the simplest demands of sport-specific training.

Think of general adaptations as the foundation of a house. You wouldn’t build the walls and roof without first pouring a stable foundation. Similarly, in rehabilitation or fitness, general adaptations ensure the body has the broad capabilities to handle higher demands later.

Specific Adaptations

Specific adaptations, on the other hand, are tailored to the unique demands of an athlete’s sport or an upcoming competition. These include movement patterns, work-rest ratios, and technical skills. For example, a soccer player needs lateral agility and quick sprint recovery, while a basketball player requires explosive vertical jumps and court-specific movements. Specific adaptations take the foundation built during general training and shape it into a form suited for competition.

Joel Jamieson emphasizes that specific adaptations cannot exist without the general foundation. An athlete might excel in one specific quality, such as vertical jump height, but struggle with endurance or recovery due to a lack of broad conditioning. This gap often results in performance inconsistencies or injury risk.

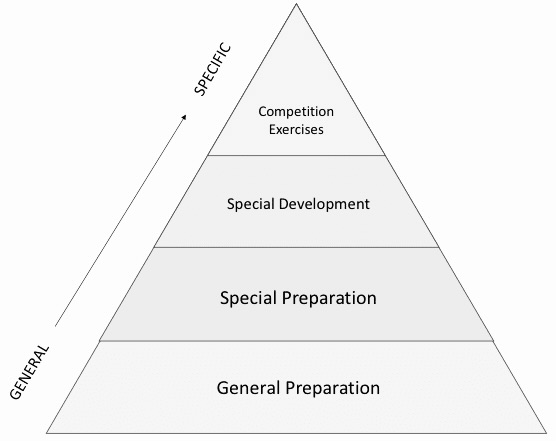

The Continuum: Progressing from General to Specific

The journey from general adaptations to specific performance is not a leap but a continuum. Each phase builds upon the last, ensuring the athlete’s readiness for the next stage of training or rehab. Here is how this progression typically unfolds:

Step 1: General Adaptations

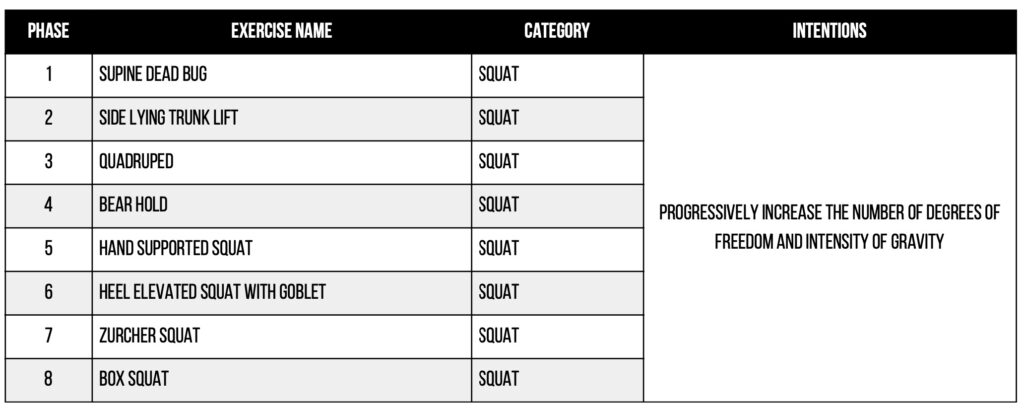

The initial phase focuses on rebuilding or maintaining aerobic capacity, general strength, and mobility. For example, following an ACL reconstruction, early conditioning might involve stationary cycling, swimming, or low intensity sled pushing to improve aerobic fitness without overly stressing the knee. General strength work, such as upper-body exercises, can also maintain overall strength capacity as an adjunct to lower body rehab.

Step 2: Transitional Phase

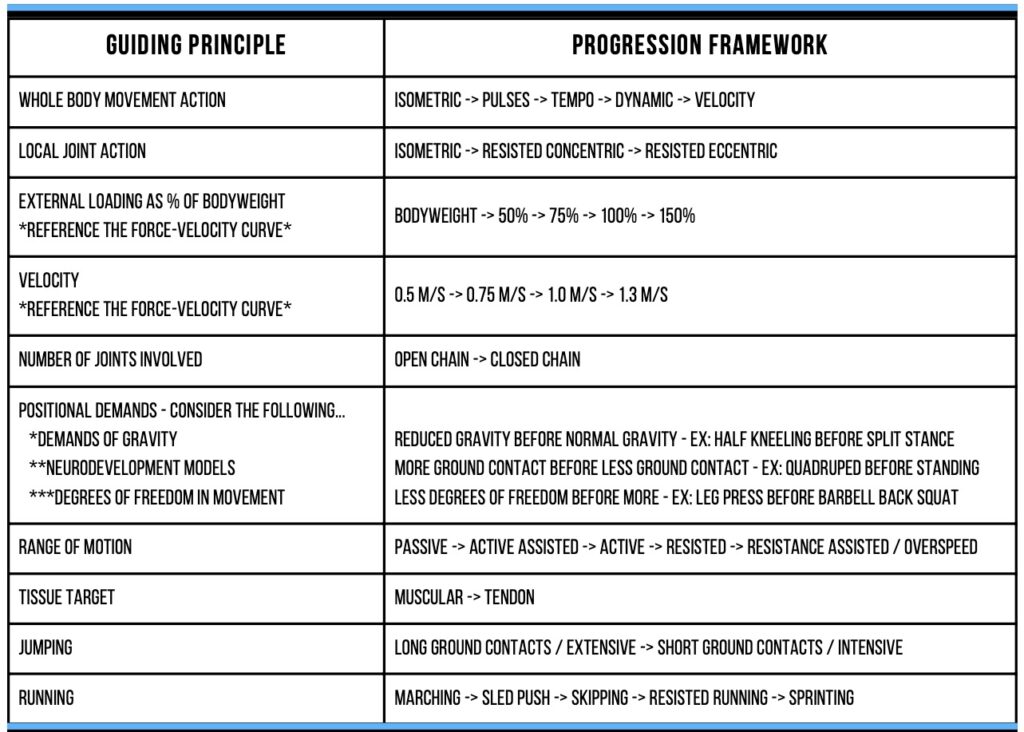

As the athlete progresses, conditioning becomes more specific to movement patterns and energy demands. This phase might include light resistance exercises like bodyweight squats, tempo-controlled strength training, or interval cycling. These activities begin to prepare the athlete for the dynamic demands of their sport while still avoiding excessive stress on the injured tissue.

Step 3: Sport-Specific Training

In the final phase, training replicates the specific demands of the sport. For a soccer player, this could involve lateral cutting drills, sprint intervals, or small-sided games. Basketball players might focus on explosive sprints, reactive agility drills, or plyometric jumps. At this stage, the athlete transitions from general preparedness to competition readiness, ensuring their conditioning aligns with the technical and tactical demands of their sport.

Physiological Foundations: Why General Adaptations Are Essential

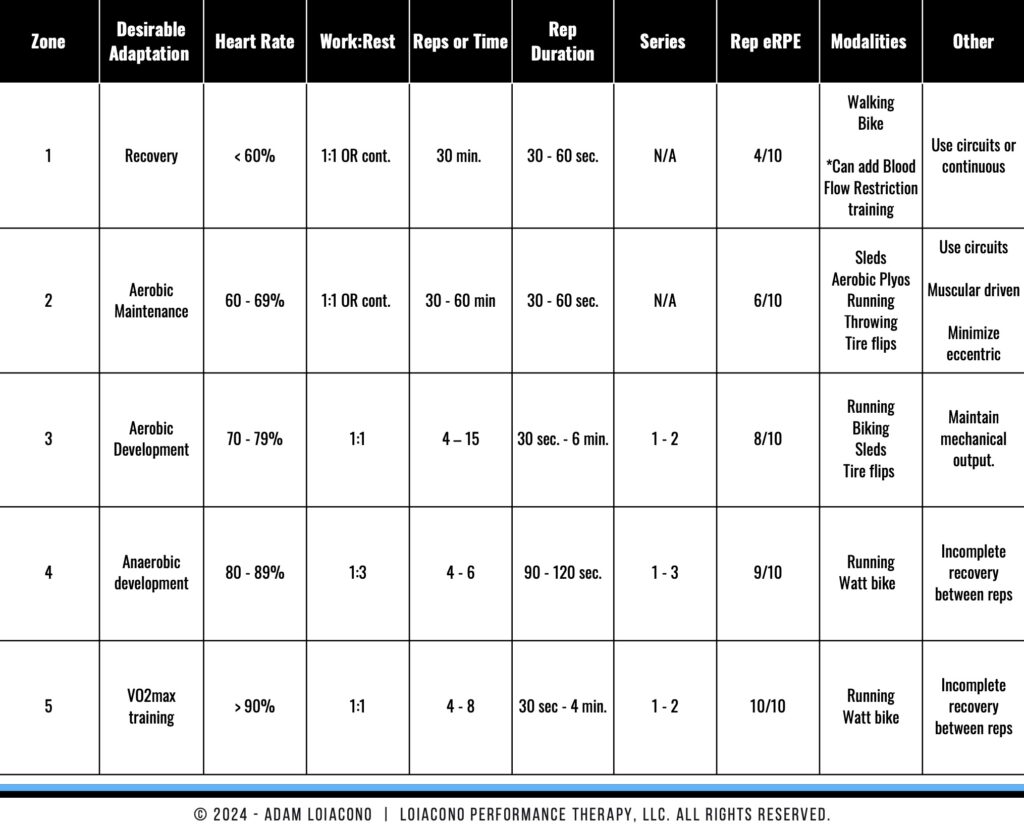

Energy System Development

The aerobic system underpins nearly all forms of physical performance, even in anaerobic-dominant sports. From the podcast episode with Joel, he highlights resting heart rate as a marker of aerobic fitness. For example, athletes with a low resting heart rate (upper 40s to low-50s) recover faster between efforts, making them more resilient during training and competition.

Aerobic fitness acts like a fuel-efficient engine, allowing athletes to perform repeated high-intensity efforts with less fatigue. Without this foundation, athletes struggle to sustain the workload needed for effective training or competition.

Muscle Adaptations

General strength training rebuilds muscle capacity and prepares the body for future stress. Exercises like split squats, leg presses, or tempo-controlled movements (e.g., 2 seconds down, 2-second hold, 2 seconds up) enhance muscle endurance and eccentric strength, key components in preventing re-injury. For example, an ACL rehab program might emphasize controlled single-leg movements to restore strength and stability before introducing dynamic drills.

Neuromuscular Coordination

General training also re-establishes motor control and coordination, which are often disrupted after injury. The principle of Movement Coordination from my 3P Injury Prevention Toolkit underscores the importance of regaining efficient movement patterns. Early-stage exercises, such as table exercises or bodyweight training, lay the groundwork for more complex tasks in later phases.

Sport-Specific Adaptations: Connecting Fitness to Performance

Specific Movement Patterns

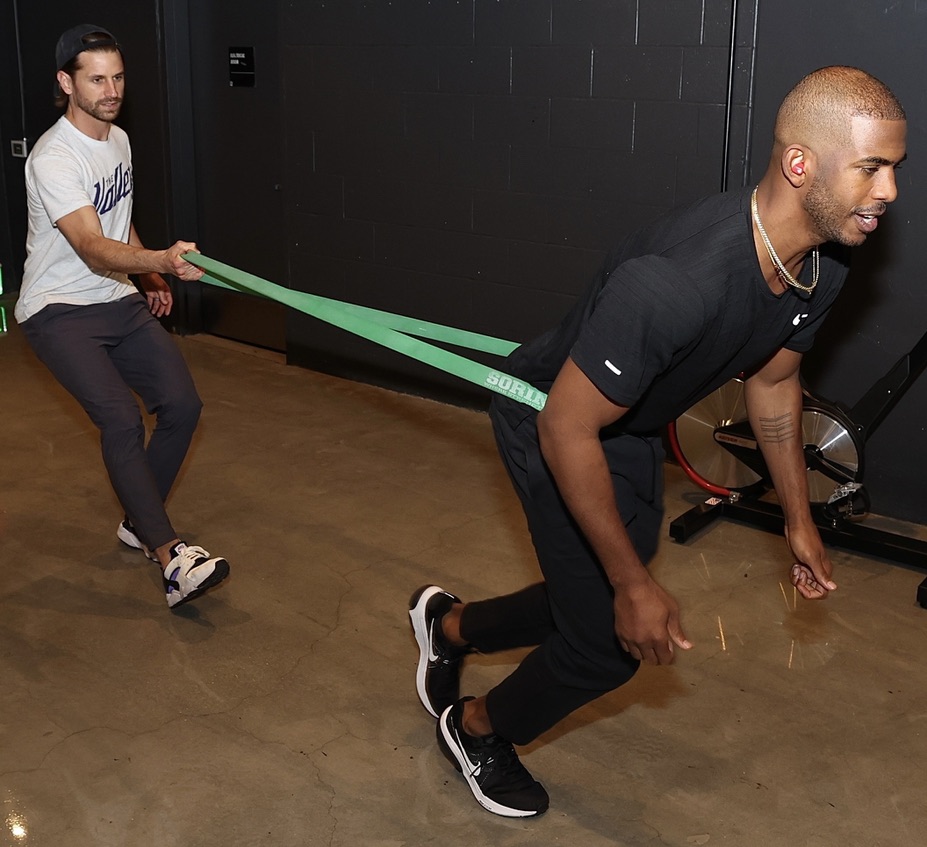

As athletes advance in their rehabilitation, conditioning transitions to mimic sport-specific movements. For example, a soccer player recovering from a hamstring strain might progress from straight-line jogging to lateral agility drills and reactive sprints. These activities not only rebuild physical capacity but also reinforce the neuromuscular patterns required in competition.

Work-Rest Ratios

Every sport has unique demands for effort and recovery. Basketball players, for instance, require repeated short bursts of high-intensity effort with brief rest periods. Conditioning programs must reflect these demands by incorporating interval training with similar work-rest ratios. For example, 30 seconds of maximal effort followed by 90 seconds of rest might mimic the energy demands of a basketball game.

Skill Integration

Finally, sport-specific conditioning integrates technical and tactical skills. For example, soccer drills that combine dribbling, passing, and agility work simultaneously develop fitness and game-related skills. This integration ensures that conditioning directly translates to performance, bridging the gap between training and competition.

Practical Applications for Return-to-Play Conditioning

Phase 1: Early Recovery

- Focus: Build general capacity while protecting the injured area.

- Methods: Low-impact aerobic exercises (e.g., cycling, swimming), light mobility work, upper-body strength training.

- Metrics: Resting heart rate and HRV to monitor recovery and readiness.

Phase 2: Mid-Rehabilitation

- Focus: Transition to functional movements and moderate intensity.

- Methods: Tempo-controlled strength training, circutis, interval cycling or pool running.

- Metrics: Heart rate recovery and HRV stability to guide progression.

Phase 3: Late Rehabilitation

- Focus: Integrate sport-specific drills and high-intensity conditioning.

- Methods: Small-sided games, reactive agility drills, sprint intervals.

- Metrics: Sport-specific metrics (e.g., jump height, 30m sprint test) to assess readiness for competition.

Challenges and Common Mistakes in Conditioning Progression

Mistakes to Avoid

- Skipping General Adaptations: Jumping to sport-specific training too early increases the risk of re-injury.

- Overloading Intensity: Introducing high-intensity work before building a foundation of volume compromises recovery and performance.

- Poor Communication: Lack of collaboration between therapists and coaches can result in mismatched goals and improper progression.

Tips for Success

- Regularly assess progress using conditioning metrics such as HRV, VO2 max, and agility performance.

- Set clear benchmarks for each phase of training.

- Emphasize gradual exposure to higher-intensity work, allowing time for adaptation.

Conclusion

The journey from rehabilitation to peak performance hinges on understanding and applying the continuum of general and specific adaptations. By building a strong foundation of aerobic fitness, strength, and coordination, athletes are better prepared to handle the demands of sport-specific training. Joel Jamieson’s insights and Adam Loiacono’s 3P Framework provide valuable strategies for structuring conditioning programs that optimize recovery and performance. When executed thoughtfully, this progression not only reduces the risk of re-injury but also ensures athletes are ready to compete at their highest level.

Finding Small Wins Podcast!

Tune into the latest episode to learn how to improve fitness and ways to monitor progress using heart rate recovery and heart rate variability.