Approximate Read Time: 12 Minutes

“Conditioning for rehab is the integration of knowledge-based physiology and the creative process of smart training choices.

What You will learn

- Respect biology first, then program for performance gains.

- Use residual training effects to guide frequency and priorities.

- Maintain fitness with safe, sport-specific alternative modalities.

Understanding the Balance Between Healing and Fitness

Injuries happen—even with the best prevention strategies. Whether it’s a high-performance athlete or a weekend competitor, recovery time can either be a setback or a strategic opportunity to return stronger than before.

In the NBA, where players face 3–4 games per week, timelines dictate strategy. If return-to-play is less than two weeks, my focus is simple: get them back to game readiness fast. If the timeline is greater than two weeks, we shift toward maintaining fitness alongside injury-specific rehab.

This approach blends biological healing rates, injury constraints, residual training effects, and periodization of stressors into one integrated rehab framework.

Biological Healing Rates: Why Biology Comes First

Before thinking about sport-specific drills or performance work, we respect the body’s built-in recovery clocks. Cold plunges, red light therapy, or specialized nutrition may help, but tissue healing timelines remain remarkably consistent.

“Biology always wins—criteria matter, but healing rates set the outer boundaries.”

Early rehab phases are criteria-driven and biology-driven. For example, I once had an NBA player four months post-ACL reconstruction. His quadriceps strength, knee range of motion, and clinical exam said “Go” for jumping and running. But meniscus healing timelines told us “Wait.” We held those activities until six months—an unpopular but correct decision supported by science.

Table 1 below summarizes tissue healing timelines based on current literature and clinical experience. These timelines are your guardrails for safe progression.

| Diagnosis | Biological tissue healing time | Tissue type |

| Ankle Sprain (Grade I) | 1-3 weeks1,2 | Ligament |

| Ankle Sprain (Grade II) | 4-6 weeks1,2 | Ligament |

| Ankle Sprain (Grade III) | 6-12 weeks1,2 | Ligament |

| ACL tear/surgery | 3-6 months3 | Ligament |

| Patellar tendonitis | 3-6 weeks4 | Tendon |

| Achilles tendonitis | 3-6 weeks5 | Tendon |

| Muscle Strain (Grade I) | 7-10 days6 | Muscle |

| Muscle Strain (Grade II) | 2-3 weeks6 | Muscle |

| Muscle Strain (Grade III) | 4-6 weeks6 | Muscle |

| Meniscus repair | Initial healing (NWB) = 4-6 weeks7 Transitional phase = 4-12 weeks7 Remodeling = 3-6 months7 | Cartilage |

| Bone fracture | 6-8+ weeks8 | Bone |

| Medial Epicondylitis | 6-12 weeks9 | Ligament |

Injury Constraints: Seeing the Whole System

Every movement is interconnected. You can’t simply “offload” one limb without consequences elsewhere.

Example:

- Bench pressing may seem knee-neutral, but the grounded leg stabilizes the thorax.

- A rear-foot elevated split squat might shift unexpected load to the injured leg if center of mass isn’t managed.

This is why integrated biomechanics must guide exercise selection during rehab. It’s not just about avoiding pain—it’s about avoiding subtle compensations that slow healing or create new issues.

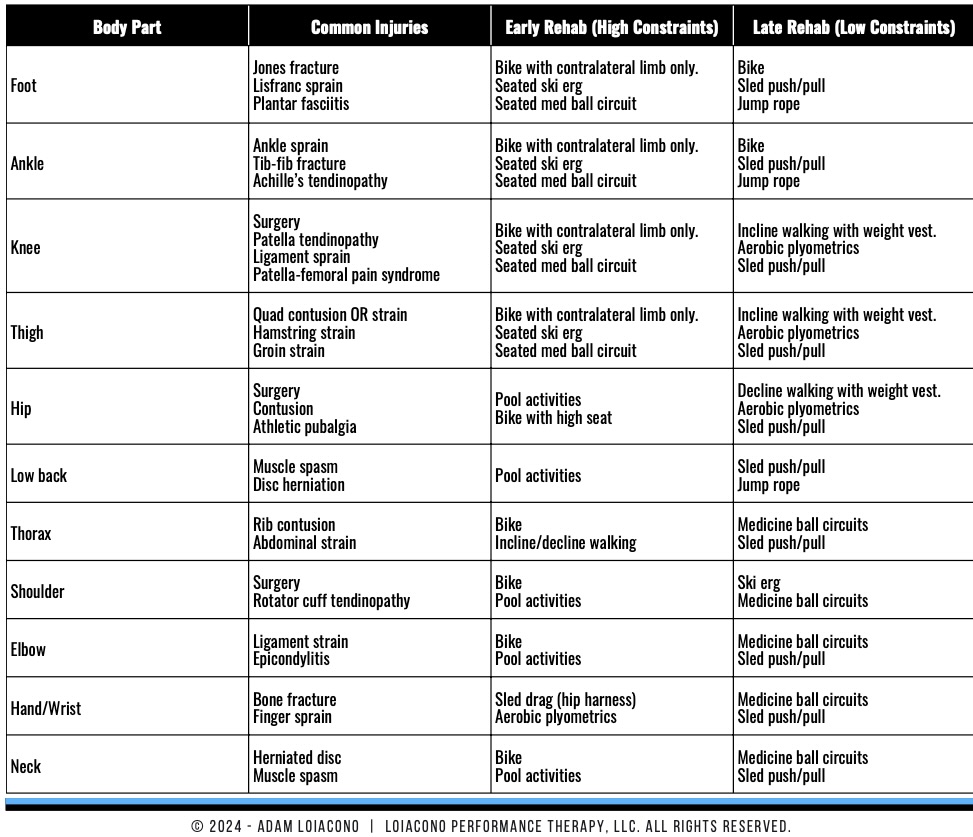

Table 2 lists alternative conditioning modalities by injury type, showing safe ways to keep athletes active through every phase of rehab.

Residual Training Effects: Programming for Retention

“Train what fades fastest—speed and power today, strength and endurance tomorrow.”

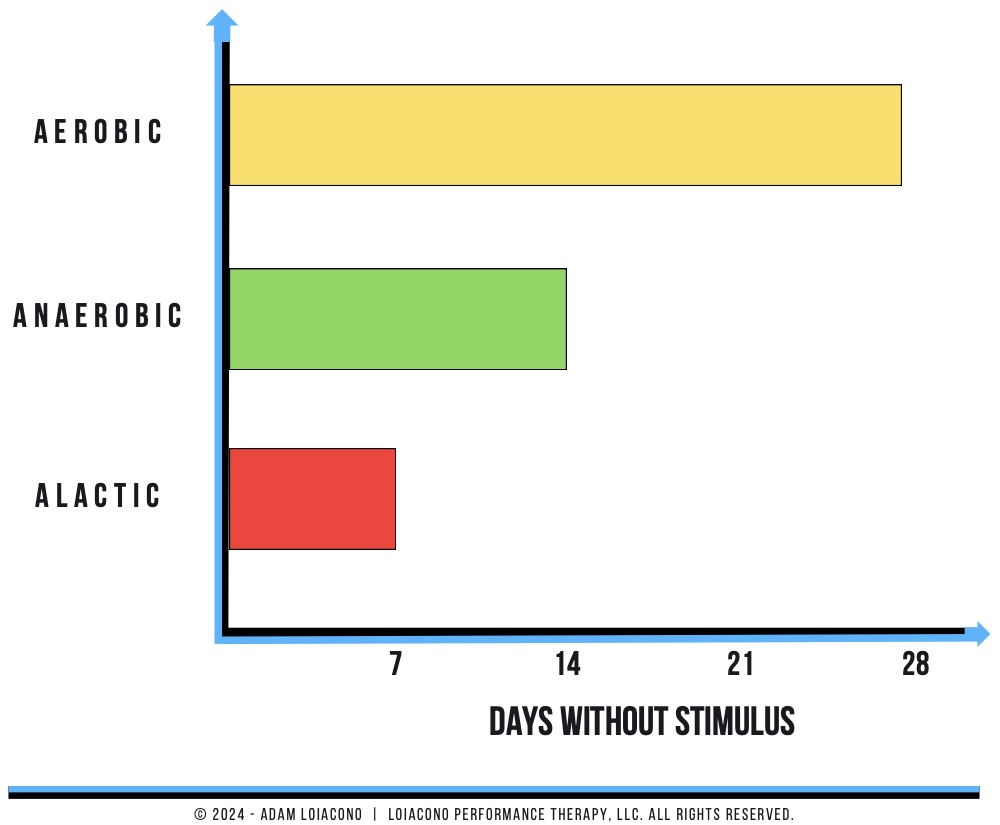

A residual training effect is how long a performance quality lasts before it starts to decline without training. For example:

| System/Quality | Residual Effect (days) |

| Aerobic Energy System | 30 ± 5 |

| Strength | 30 ± 5 |

| Anaerobic Energy System | 18 ± 4 |

| Power | 15 ± 5 |

| Creatine-Phosphate System | 5 ± 3 |

| Speed | 5 ± 3 |

If speed is lost quickly, it takes priority over qualities with longer residuals. This insight helps determine frequency, even during limited rehab windows.

Table 3 outlines residual timelines for common physical qualities, guiding decisions on what to train and when.

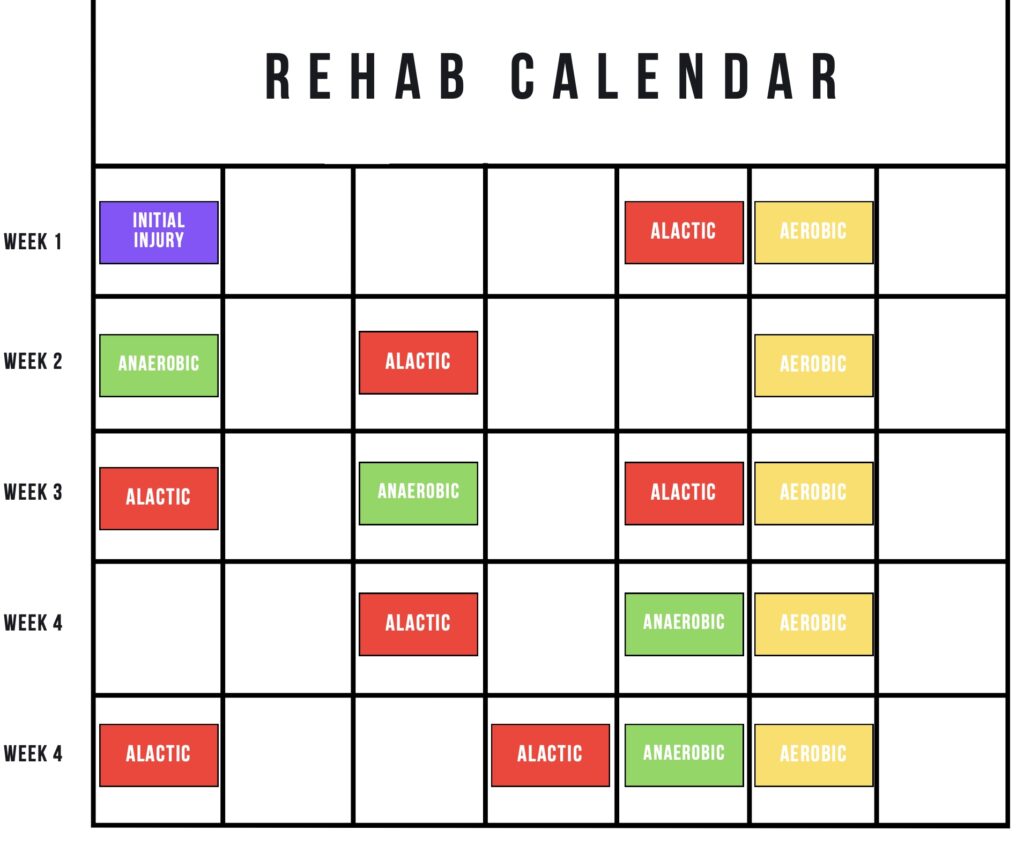

Periodization: Merging Science with the Calendar

Combining healing rates, constraints, and residual effects creates a roadmap for periodized rehab.

In a long-term post-surgical knee case, weeks 0–8 were pure tissue protection. From weeks 8–12, we strategically reintroduced performance qualities:

- Power & speed every 3–4 days (medicine ball circuits, assisted jumps)

- Aerobic work with blood flow restriction (BFR) to amplify metabolic and healing effects

- Strength once weekly, alternating upper and lower body

Even with performance sessions on five of seven days, volume stayed low to keep tissue recovery the priority.

Athletes crave the feeling of “work.” While aerobic adaptations may last a month, frequent low-load BFR sessions help them sweat, maintain rhythm, and boost morale. Sometimes, the best choice isn’t purely physiological—it’s psychological.

Conditioning for Rehab: Final Thoughts

Rehab is not just training with modifications. It’s a layered, science-backed process that respects healing biology while minimizing fitness loss. By integrating:

- Biological healing timelines

- Constraint-led exercise selection

- Residual training effects

- Periodized stress exposure

Free Download

Watch More Like This

Read More Like This

Related Podcasts

References

Maughan KL. Acute Ankle Sprain: An Update. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(10):1714-1720.

Martin RL, et al. Ankle Stability and Movement Coordination Impairments: Ankle Ligament Sprains. JOSPT. 2013;43(9):A1-A40. doi:10.2519/jospt.2013.0305.

Adams D, et al. Current Concepts for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. JOSPT. 2012;42(7):601–614. doi:10.2519/jospt.2012.3871.

Maffulli N, et al. Types and Epidemiology of Tendonopathy. Clin Sports Med. 2003;22(4):675-692.

Carcia CR, et al. Achilles Tendonitis: JOSPT. 2010;40(9):A1-A26.

Fernandes TL, et al. Muscle Injury – Physiopathology, Diagnosis, Treatment and Clinical Presentation. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;46(3):247–255. doi:10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30190-7.

Reinold M, et al. Rehabilitation Following Articular Cartilage Repair Procedures in the Knee. JOSPT. 2006;36:744-794.

Marsell R, Einhorn TA. The Biology of Fracture Healing. Injury. 2011;42(6):551–555. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.031.

Amin NH, et al. Medial Epicondylitis: Evaluation and Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(6):348–355.

Issurin VB, Yessis MA. Block Periodization: Breakthrough in Sport Training. Ultimate Athlete Concepts; 2008.