“The human body doesn’t know conditioning on a bike or from a circuit with a sled – it just knows stress & physiology.”

Adam Loiacono

What You Will Learn

- What is the traditional terminology for conditioning?

- How to optimize the minimum effective dose to maintain conditioning?

- Effective modalities for enhancing conditioning during sports rehab.

Traditional terminology

Physical conditioning plays a crucial role in sports rehabilitation, aiding athletes in recovering from injuries and returning to their peak performance. It involves a careful blend of exercises, monitoring, and understanding of the body’s responses, particularly in terms of heart rate zones and energy systems. This post delves into these aspects, offering insights for trainers, therapists, and athletes alike.

Understanding Heart Rate Zones

There are many perspectives on what heart rate zones are and what each range is targeting. A classic model that you will see from companies like Polar or your Apple watch are 5 zones. I’ve seen other companies like OmegaWave use 7-8 zones. After years of training myself and working with professional athletes, I find myself using 3 keys zones to keep things simple and effective. Within the classic model, these zones are 2, 4, and 5.

- Zone 2 (60 – 70% of max HR): classicaly known as Zone 2 (popularized by health experts Dr. Peter Attia and Dr. Andrew Huberman). This zone is meant to improve endurance by increasing the compliance of the ventricular walls. The slower heart rate allows time for the ventricles to maximally expand, which then increases stroke volume and cardiac output. This intensity is also low enough that cellular metabolite accumulation is not exceeding the ability to clear the metabolites. The focus of enduring this type of training is by delivering oxygen to the working cells. This is commonly known as Aerobic Development – the presence of oxygen. The common metric you will see change with this type of training is a lower resting heart rate.

- Zone 4 (80 – 90% of max HR): improve endurance by increasing the buffering systems within the body to clear the accumulation of cellular metabolites. At this intensity the body is producing more metabolites then it can clear and produces the sensation of “legs on fire.” This is commonly known as Anaerobic Development – the absence of oxygen. The feeling of “legs on fire” is the accumulation of hydrogen molecules and other metabolites in your bloodstream that reduces the blood pH to be more acidic.

- Zone 5 (> 90% of max HR): improve maximal V02 max. This is the zone that is brutal and challenging to maintain for long periods, but is necessary in order to develop fitness. Most intervals in the phase for team sport athlete is anywhere from 1 – 6 minutes. It addresses not only increasing cardiac output and the ability to buffer cellular metabolites, but also addresses power outputs. Power outputs could be watts on a bike or a particular speed while running. This type of training is typically achieved through running for most athletes. If you are an experienced cyclist you may be able to get into this zone. Most athletes I have worked with complain of leg fatigue before they are able to achieve this heart rate zone.

Energy Systems in the Body

Physical conditioning can be reduced down to two key processes – deliver oxygen & buffer hydrogen.

Adam Loiacono

The body relies on three primary energy systems, each playing a unique role in physical activity. Commonly we discuss each of these systems isolation BUT it is imperative that we understand that all systems are working together during activity.

ATP-PC System:

The ATP-PC System, also known as the phosphagen system, is the body’s primary method for generating energy in activities requiring quick, high-intensity bursts lasting up to 10 seconds. It uses adenosine triphosphate (ATP) stored in muscles and phosphocreatine (PC) for immediate energy production. This system functions without the need for oxygen and is crucial for explosive activities like sprinting or heavy lifting. Due to its rapid energy release, the ATP-PC System is the first to be engaged in high-intensity exercises, but it exhausts quickly, necessitating brief activity periods followed by rest to replenish energy stores.

FUN FACT: creatine supplementation targets ATP-PC stores.

Glycolytic System

The Glycolytic System, also known as the anaerobic system, is an energy system that kicks in for moderate to high-intensity activities lasting from about 30 seconds to 2 minutes. This system breaks down glucose, sourced either from blood sugar or muscle glycogen, into pyruvate, producing energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Unlike the ATP-PC system, the glycolytic system can sustain energy production for a longer duration but generates lactic acid as a byproduct, leading to muscle fatigue and soreness. It’s essential for activities like middle-distance running, swimming, or high-intensity interval training (HIIT).

Oxidative System

The Oxidative System, also known as the aerobic system, is the primary energy source for prolonged, low to moderate intensity activities. It utilizes oxygen to metabolically convert carbohydrates, fats, and sometimes proteins into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy currency of cells. This system is most active during extended exercises like long-distance running, cycling, or swimming. Although it generates energy more slowly than the ATP-PC and Glycolytic systems, the Oxidative System can sustain energy production for a significantly longer duration, making it crucial for endurance sports. It also produces less lactic acid, reducing muscle fatigue during prolonged activities.

Conditioning Guidelines

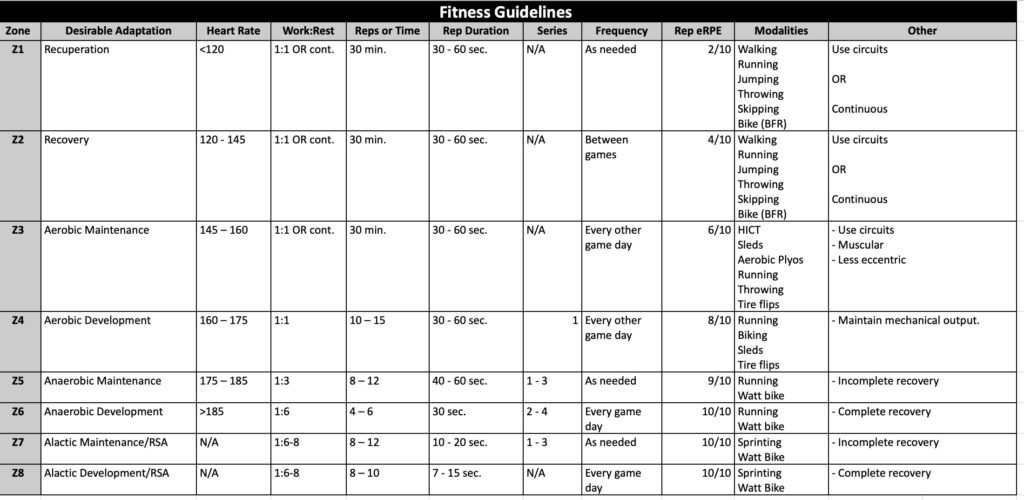

Below is a sample of how I think about manipulating sets, reps, and time intervals when programming conditioning. This particular references the OmegaWave model of 8 zones. I created this table to show how subtle differences in HR or rep duration can target very specific qualities.

In general, low intensity targets the aerobic system. Moderate intensity targets the anaerobic system. Finally, high intensity can target either alactic or aerobic depending the duration of the interval. This table is not comprehensive and is based on general guidelines irrespective of sport specificity.

How to integrate conditioning into rehab

The first thing I think about when implementing conditioning into a sports rehab case is the rate of decay of the athletic quality if it is left untrained. More simply put, if I do not train a particular quality for ‘X’ number of days, how long will it be before I see a performance decrease?

Below are quick, easy timeline estimates of when we see decreases in performance relative to conditioning. These timelines are based on if we were not to provide a particular stimulus, then it would take “X” amount of weeks before we start to see a performance decline of that specific quality.

- Alactic: 1 week

- Anaerobic: 2 weeks

- Aerobic: 4 weeks

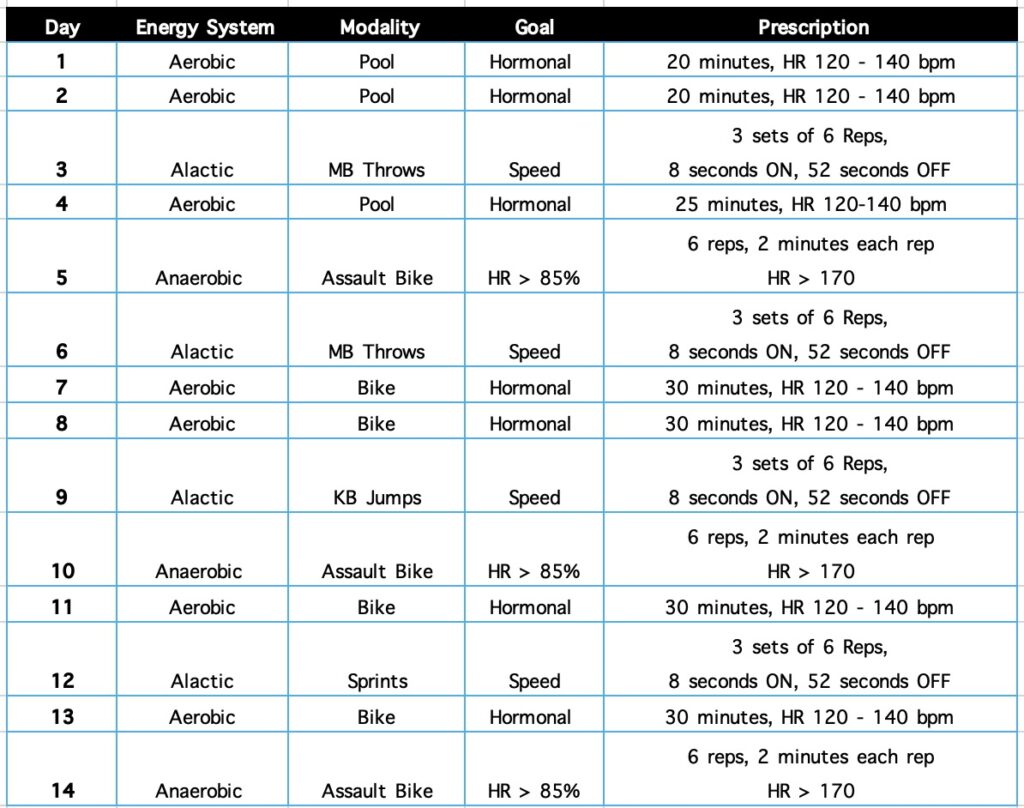

The next step I take is trying to hit the minimum effective dose in order to maintain each quality based on the above timelines. For example, if Alactic has a drop off at 7 days, then during my rehab plan I am structuring an Alactic session every 6-7 days. Then I will do the same for each of the other two energy systems to help minimize any performance deficits during the rehab process. Below is a sample conditioning program for a 2-week lateral ankle sprain:

How to Use the Sport to Improve Fitness

In this short video, I discuss how we can manipulate a few variables during sport to target specific energy systems. The key variables to manipulate are the size of the playing space and the number of players.

Additional resources

Ultimate MMA Conditioning by Joel Jamieson – my GO TO resource for refreshers and new ideas for improving athletic conditioning

Applied Sprint Training by James Smith – a simple yet effective book for understanding foundational principles for sprint training.