Approximate Read Time: 8 minutes

Even with world-class preparation and top-tier medical support, ankle sprains remind us: injuries are often unpredictable.

What You will learn

- Ankle sprains can happen to anyone and recovery requires more than rest and ice

- Ligaments provide passive stability but muscles create active control and must be rebuilt during rehab

- Return to play timelines depend on injury severity and not all ankle sprains heal at the same pace

- Early movement circulation techniques and progressive loading strategies accelerate healing and recovery

- True ankle rehab requires multi-angle proprioceptive training not just balance pads or slow movements

Even the Best Can Roll an Ankle

In 2023, during the much-anticipated home debut of Kevin Durant for the Phoenix Suns, an unexpected moment unfolded — he rolled his ankle during warm-ups. No collision. No awkward landing. Just the floor and a twist of fate. That was an unfortunate moment in the training room having to update the head coach and general manager that he would not be available. Needless to say, everyone felt a bit deflated.

Having spent 7 season in the NBA, I’ve seen firsthand that ankle sprains are among the most common, frustrating, and sometimes misunderstood injuries athletes face. In this article, we’ll explore why ankle sprains happen, how we can manage them better, and why rehab must address the entire system, not just the ligament.

The Anatomy Behind Ankle Stability

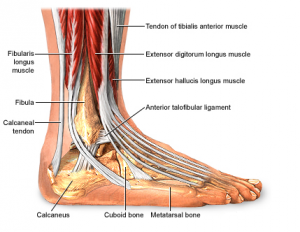

Ligaments act as passive restraints, but dynamic stability comes from the extrinsic muscles providing active compression and control.

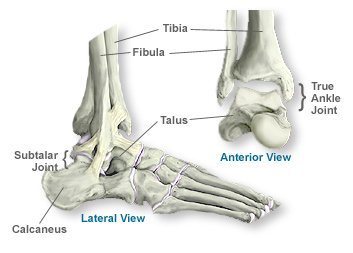

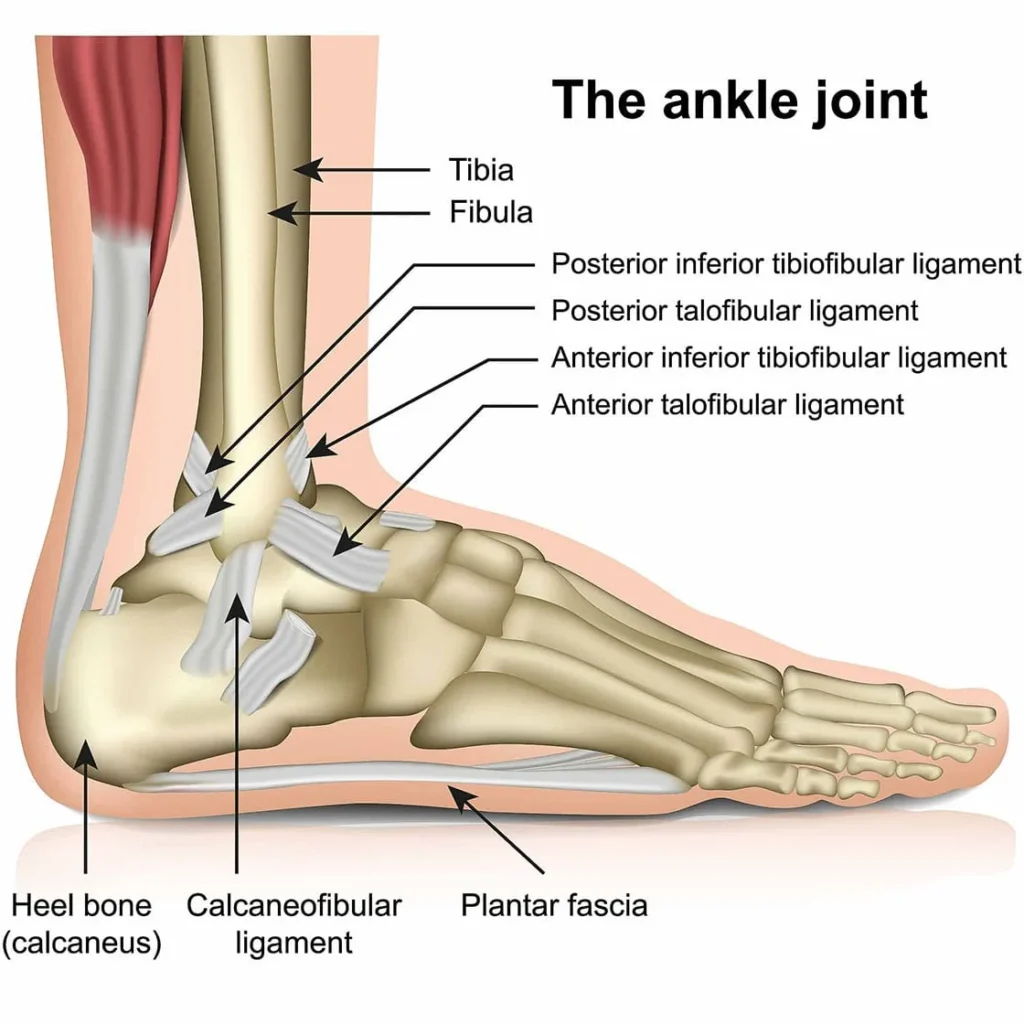

The ankle joint, often compared to a wrench gripping a bolt, relies on a complex structure for stability:

- Bones: Tibia and fibula create a mortise around the talus—like a wrench around a bolt.

- Ligaments:

- Anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) — most commonly injured.

- Calcaneofibular ligament (CFL)

- Posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL)

- Muscle Compartments:

- Anterior: Tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus (dorsiflexors)

- Lateral: Peroneals (evertors)

- Posterior Superficial: Gastrocnemius, soleus (plantarflexors)

- Posterior Deep: Tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, flexor hallucis longus (invertors)

Treat the Person, Not Just the Diagnosis

A sprained ligament is only part of the story. True rehab success means rebuilding the entire system — proprioception, neuromuscular control, strength, and coordination. Ligament healing alone does not guarantee an athlete can cut, jump, land, or sprint the way they need to in competition. Without restoring the dynamic components of movement, the risk of reinjury remains high even if the ankle “feels better.”

This philosophy reflects Principle 9: Treat the Person, Not the Diagnosis from my 3P Framework. Each athlete brings a unique blend of tissue healing, movement strategies, psychological readiness, and previous injury history that influences recovery. It’s not enough to simply monitor swelling or pain levels — the real goal is to rebuild functional capacity at every level: local tissue strength, joint integrity, system-wide coordination, and sport-specific demands.

When we shift our mindset from treating just the ankle to treating the athlete, we prioritize long-term resilience over short-term symptom resolution. True function means the athlete can generate force, absorb force, and adapt to unpredictable environments — not just pass an isolated balance test or tolerate jogging. Rehabilitation must rebuild the physical and neural systems that enable athletes to move powerfully, react instinctively, and perform confidently under game conditions.

The 10 Principles of my 3P Framework (Principles, Process, and Plans)

- Coordinate Movement

- Force Management

- Fitness

- Commit & Learn

- Context Matters

- N=1

- Prioritize & Simplify

- Invest in Preparation, Not Prediction

- Treat the Person, Not the Diagnosis

- Consistency is King

Recovery Timelines

Not all ankle sprains are created equal. Here’s a research-backed snapshot:

| Grade | Definition | Avg Return to Sport |

|---|---|---|

| Grade I | Mild, no ligament laxity | ~7 days |

| Grade II | Moderate, partial ligament tear | ~15 days |

| Grade IIIA | Complete tear, less than 3mm anterior displacement | ~31 days |

| Grade IIIB | Complete tear, more than 3mm displacement | ~55 days |

The severity of the ligament injury directly impacts the recovery timeline and the rehabilitation approach. A mild Grade I sprain typically involves microscopic tearing with minimal instability, allowing for quicker recovery and return to activity. Grade II sprains, with partial ligament tears, often present with more swelling, bruising, and functional limitations, requiring a more cautious progression. Grade III sprains involve complete ligament ruptures, significant instability, and sometimes multiple ligaments, leading to the longest recovery times and the greatest need for structured rehabilitation to rebuild both passive and dynamic stability. Understanding the specific grade of injury is crucial to setting realistic expectations and designing an effective return-to-play plan.

Key Factors The Can Delay Recovery

Certain injury characteristics can signal a longer and more complicated recovery following an ankle sprain. Significant swelling, often measured by more than a 2 cm difference using the figure-8 method, indicates greater tissue trauma and inflammation. Severe pain at rest is another important indicator, suggesting deeper ligamentous disruption or associated soft tissue involvement beyond a simple sprain.

Early inability to bear weight and multiligament involvement, particularly when both the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) and calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) are affected, further increase the likelihood of a prolonged rehabilitation process. These factors often correlate with higher grades of sprain severity and greater instability, requiring a more cautious and progressive approach to recovery. Recognizing these signs early allows clinicians and athletes to better calibrate expectations, customize treatment plans, and avoid premature return to play.

Early Management Matters: Two Game-Changing Strategies

1. Banded Stretch Traction

Research shows early mobilization techniques, like banded ankle traction, accelerate pain-free motion without increasing instability.

- Improves talocrural joint mobility

- Reduces swelling through enhanced drainage

- Promotes safer, faster functional loading

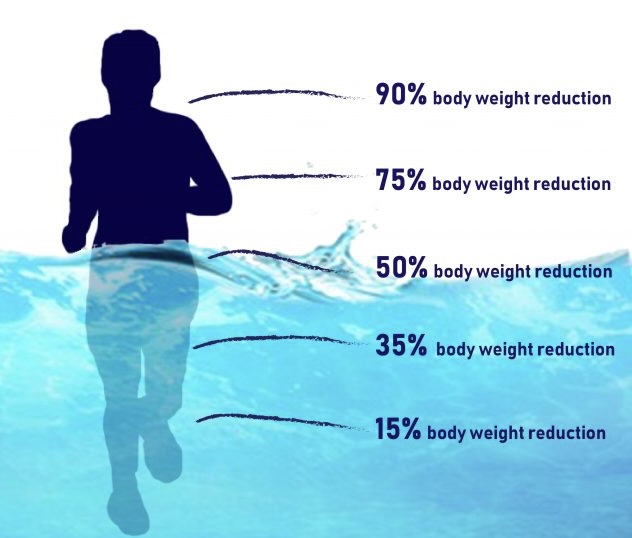

2. Aquatic (Pool-Based) Rehab

Water immersion isn’t just gentle — it’s strategic:

| Water Depth | Approx. Body Weight Offloaded |

| Neck-deep | 90% offloaded |

| Chest-deep | 70–75% offloaded |

| Waist-deep | 50% offloaded |

Plus, hydrostatic pressure acts like a natural compression garment, promoting circulation and minimizing swelling.

When the body is submerged in water, pressure is exerted evenly across the skin and tissues, with greater pressure at deeper depths. This consistent compression helps push excess fluid from the injured area back into the circulatory system, improving venous return and lymphatic drainage.

Research shows that hydrostatic pressure can reduce edema, lower heart rate, and enhance nutrient delivery to healing tissues without adding mechanical stress to joints. In practical terms, this means faster resolution of swelling, less congestion around the ankle, and a more efficient recovery environment — all while offloading weight during movement.

Pro Tips to Accelerate Ankle Recovery

Pro Tip 1:

Use whole limb compression + MarcPro stimulation immediately to limit swelling and promote muscle pump action.

Pro Tip 2:

Start isometric exercises by Day 2. Pain-free isometric contractions help restore dynamic ankle stability early.

Pro Tip 3:

Incorporate BFR (Blood Flow Restriction) training for the lower leg to safely drive muscle activation and hypertrophy without heavy loads.

Pro Tip 4:

Sleep with FireFly units on to maintain circulation overnight and prevent fluid stasis.

Pro Tip 5:

Train proprioception beyond foam pads. Use multi-angle plyometrics and isometrics on slanted surfaces, and challenge balance without looking at your feet—training the vestibular and proprioceptive systems, not just visual cues.

Myth Buster: Foam Pads Aren’t Enough

Foam pads and BOSU balls are great for early confidence-building — but they don’t sufficiently prepare athletes for real-world demands.

True proprioceptive recovery happens when athletes are exposed to multi-plane, multi-angle, multi-speed forces—not just slow balance on a soft surface.

→ Bonus tip: Force athletes to keep their head up — no looking at the ground — to fully stimulate proprioception, vestibular, and somatosensory integration.

Conclusion: Ankle Sprains Demand a Systematic, Whole-Person Strategy

Even the world’s best athletes can’t predict when an ankle sprain will occur. But we can control how we respond.

By restoring not just joint integrity, but muscle, movement, and mind, we can build athletes who don’t just return — they come back better.

Accelerate Ankle Sprain Rehab

Listen to this episode of Finding Small Wins: “Rethinking Recovery, Stiffness, and Circulation with Anthony Kjenstad” where we explore creative ways to accelerate recovery after lower leg injuries.

References

- Iammarino K, Marrie J, Selhorst M, et al. Efficacy of the Stretch Band Ankle Traction Technique in the Treatment of Pediatric Patients With Acute Ankle Sprains: A Randomized Control Trial. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018;13(1):1-11.

- D’Hooghe P, Cruz F, Alkhelaifi K. Return to Play After a Lateral Ligament Ankle Sprain. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2020;13(3):281-288.

- Thompson JY, Byrne C, Williams MA, et al. Prognostic factors for recovery following acute lateral ankle ligament sprain: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):421.

- Smith MD, et al. Return to sport decisions after an acute lateral ankle sprain injury: introducing the PAASS framework. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55(23):1270-1276.

- Martin RL, Davenport TE, Paulseth S, et al. Ankle Stability and Movement Coordination Impairments: Ankle Ligament Sprains: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the ICF From the Orthopaedic Section of the APTA. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2013;43(9):A1-A40.