Approximate Read Time: 14 minutes

“Running is high-skill, high-force movement that demands strength, rhythm, and tissue readiness. Skipping the preparation means you’re not just rushing the process—you’re risking the outcome.”

What You will learn

- Athletes often rush back into running without developing adequate strength and tissue capacity.

- Ground contact time, skipping, and rudimentary plyometric progressions are often skipped.

- Eccentric strength and deceleration readiness are underappreciated in lower body return-to-run.

- Skipping steps isn’t efficient—it’s expensive.

Running Is a Skill—Not a Milestone

Running is often treated like a checkbox in rehab—something you “get cleared” to do once the swelling is gone, the limp is gone, or the athlete is simply impatient. But running isn’t the destination. It’s a demanding skill that requires strength, rhythm, timing, and tissue readiness.

This article unpacks the 3 most common mistakes I see athletes make during return-to-run protocols—and how to avoid them. These aren’t just pet peeves. They’re patterns that lead to swelling, setbacks, and frustration. Let’s get into them.

Mistake #1: Not Getting Strong Enough

There’s a temptation to sprint before you can squat. Athletes are often eager to start jogging again, and rehab programs sometimes enable this eagerness by prioritizing movement over preparation.

But let’s be clear: Running is a high-force activity. If you don’t have the strength to absorb and redirect those forces, you’re not running efficiently.

Here’s What’s Often Missing:

- Isometric calf strength (especially post-Achilles, ankle sprain, or plantar fasciitis)

- Isokinetic hamstring/quad strength asymmetries after knee injuries

- Absolute lower body strength (e.g., trap bar deadlift, front squat)

If you skip this step, you don’t build force capacity. And without capacity, your joints compensate. That’s when you start to see swelling, irritation, or that vague sense of “I don’t feel ready.”

“Weak links don’t get exposed at 50%. They get magnified 10-fold at 90%.”

Athletes often perceive these setbacks as surprising. But it’s not a setback—it’s a signal. You skipped the load-building phase. Your tissues weren’t ready.

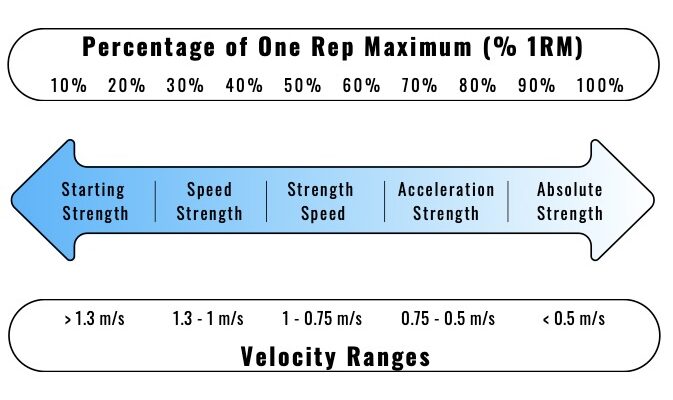

Related Reading: The Complete Guide to Velocity-Based Training in Rehab

Mistake #2: Skipping Progressions (Literally)

I’ve seen this more times than I can count: the athlete gets “cleared to jog” followed by the scenario of increases in pain and swelling. Cue the setback. No march. No skip. No dribble series.

Here’s what they’re missing:

- Marching drills to establish timing and rhythm

- Skipping to introduce bounce and coordination

- Sled pushes/pulls for low-velocity, high-force return

- Low amplitude plyometrics (e.g., rudimentary hops, bilateral to unilateral progressions)

- Short tempo runs with progressive speeds to decrease ground contact times before long-distance jogging or 1-miles runs.

“Skipping steps in your return to run isn’t efficient—it’s expensive.”

Athletes may not realize that during even a slow jog, forces of 2.5–3x bodyweight go through the limb. If your body hasn’t rehearsed absorbing and redistributing those forces through controlled hops, landings, or sled marches, you’re not preparing—you’re hoping for the best with a strong likelihood for a setback.

Related Reading: How to Progress Ground Contact Time in Sports Rehab

Mistake #3: Undervaluing Eccentric Strength and Tissue Adaptation

If you’ve ever consulted on a case where an athlete keeps flaring up post-run or has a “stubborn” patellar tendon, here’s the first question to ask:

“Have you tested their eccentric strength?”

It’s consistently one of the most overlooked elements in lower limb rehab that I come across. Eccentric-focused strength creates the tissue remodeling necessary for running, especially deceleration and initial contact during the gait cycle.

Why do athletes avoid it? Because it makes them sore. But soreness is a byproduct of adaptation. And the absence of eccentric resilience is a recipe for re-injury.

Key Applications:

- Slow eccentric single leg squats

- Nordics and eccentric step-downs

- Tempo lunges or isometric-to-eccentric transitions

Most athletes can tolerate acceleration—pushing the ground away. But they break down when they have to slow down. That’s because deceleration demands are nonlinear. They require more coordination, more tendon capacity, and more neural timing.

“Deceleration is the forgotten gear in most rehab transmissions.”

Related Reading: Deceleration Training as the Missing Link

Final Thoughts: Don’t Just Run—Earn It

Getting back to running isn’t about clearance. It’s about capacity.

Whether you’re an athlete, coach, or rehab pro, the message is the same: Don’t rush the progressions to chase the reward. Running is complex. It’s high force, high coordination, and high expectation.

And if you skip the “boring stuff” now, you’ll end up doing the frustrating stuff later.

For Further Listening

- Podcast: The 10×10 Sprint Test and Return to Running with Derek Hansen

- Podcast: Isokinetic Strength Training & Assessments with Daniel Bodkin