“The interesting part is that for several injuries the criteria to decide if they should or should not return to play is often gray. “

Adam Loiacono

What You Will Learn

- The 10 Principles of how to progress an athlete through rehab.

- How multiple Performents are integrated during specific phases.

- Learn how each Performent creates an opportunity to make daily progress.

Return to play. Return to sport. Return to participation. Return to performance. Return to competition. So many variations of this phrase that dignifies completing the rehabilitation process for a sports injury that ultimately results in the athlete returning to games. The interesting part is that for several injuries the criteria to decide if they should or should not return to play is often gray. This is where I have created The 10 Performents of Return to Play to create a framework for my decision-making process.

I prefer the phrase “return to play” simply because athletes play a sport. All the other buzz words are cool with me, but what I am particular on are the principles that underly our criteria to return an athlete. I believe once we are beyond the initial acute injury phase, majority of rehab cases are the same. In most situations, an athlete is going to have to return to running, jumping, changing direction, contact, and in specific sports either kicking or throwing. Therefore, I believe every decision we make needs to be directed at one of these qualities. But how?

Return to play and rehabilitation operate in such a gray space that there is high variability in what criteria needs to be met. I also acknowledge that in the environment of professional sports, the business aspect sometime supersedes the return to play criteria. In these instances, I do the best I can with the many stakeholders involved. Below is how I navigate the gray space of return to play through my 10 Performents.

10 Principles of Return to Play

1. Global Movement Action

Isometric -> Pulses -> Tempo -> Dynamic -> Velocity

Movement is a foundation to The 10 Principles. Within movement it is expected for specific ranges of motion to be limited as pain or discomfort still exist. The progressions from Isometric to Velocity are challenging not only positional demands. but also the overall density of the movement. Within exercise prescription these variables can be manipulated to have within session progressions or day to day progressions.

Isometric is holding a particular position. The Pulses phase is short movements within that specific position. The next progression is Tempo which is slow, controlled movement through full ranges of motion. The Dynamic phase is moving at a comfortable and normal speed, which I consider traditional functional movement or weight training. Velocity begins to incorporate overspeed and higher intensities that more closely resemble sport.

2. Local Movement Action

isometric -> Concentric -> Eccentric

Isometric movement actions have the ability to modulate pain. The ability to modulate pain is why I believe in incorporating isometrics first and as early as possible in this Performent. The middle ground of concentric actions is less demanding on the tissue because of the nature of shortening the tissues under load. Eccentric is the final phase of progressions because it is the most demanding and often times the action that an injury occurred in.

For example, for a hamstring strain I would start with the athlete lying on their back and performing 90-90 isometric holds. Then I would progress to them lying on their back performing only the concentric action of a leg curl on a physioball. The final phase would be performing some variation of a Nordic hamstring to challenge the eccentric.

3. Load

Bodyweight -> 50% bodyweight -> 100% bodyweight -> 150% bodyweight

Simply put – go lighter loads before heavier loads. Irrespective of bar speed, when external loads are increased force outputs tend to increase. Increasing force outputs will ultimately stress the injured tissue more.

I prefer keeping loads relative to an athlete’s bodyweight. I like to progress set-rep schemes based on percentages of bodyweight. Lighter loads that are bodyweight exercises typically have higher rep ranges (15-20 reps) versus heavier loads that are 100-150% bodyweight are lower rep ranges (3-5 reps).

During return to play Load is a variable that exists on a pendulum. Early on the loads are very light as introductory movements are executed. Then loads become very heavy as we approach absolute strength metrics. Finally, the loads become light again as we begin to manipulate speed and velocity.

4. Velocity

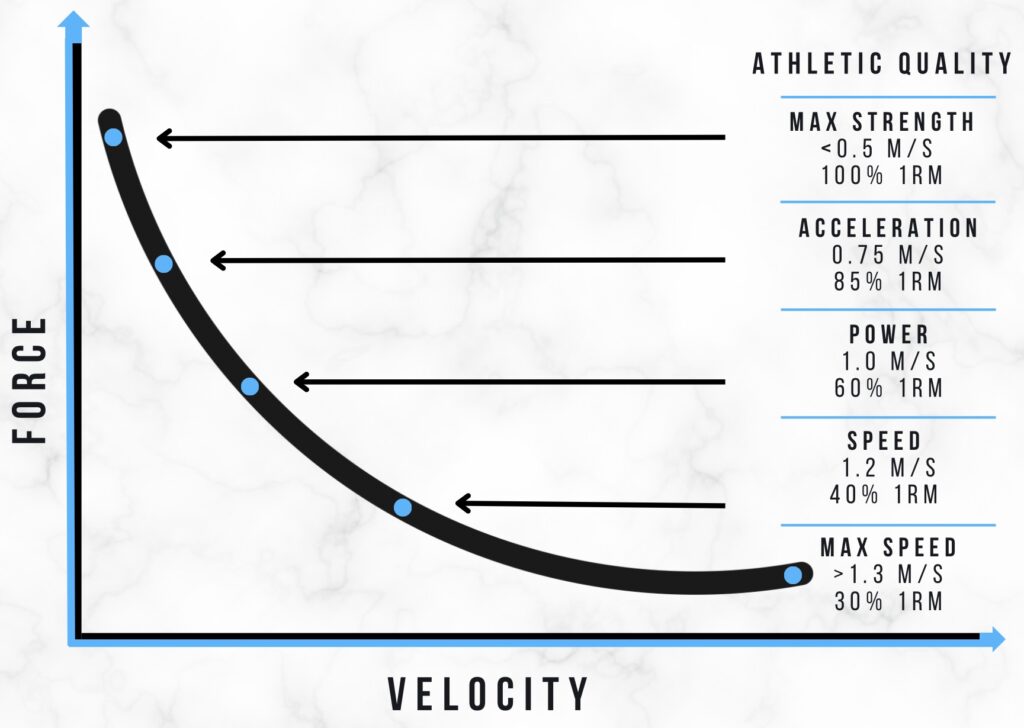

0.5 m/s -> 0.75 m/s -> 1.0 m/s -> 1.25 m/s

The 4th Performent in The 10 Performents is utilizing The Force-Velocity curve. The curve is a powerful principle that needs to be considered during rehab. Once absolute strength is established, speed is the next component to be addressed. Velocity Based Training (VBT) is how I prefer to monitor and progress this Performent during the return to play process.

Sport occurs at high velocities. Most weight room activities occur at low velocities. Lower velocities are important for laying the foundations of strength, hypertrophy, and capacity. But ultimately the neuromuscular component of speed has to be addressed. VBT is a very simple and effective tool for progressing phases of rehab to gradually expose the injured tissue to increasing velocities. Principles #3 and #4 are closely related because as Velocity begins to increase, Loads tend to decrease.

5. Kinetic Chain

Open Chain -> Closed Chain

When an injury happens there is a specific, local tissue that is compromised. The best way to load local, specific tissues is through open chain, single joint actions. If we neglect the open kinetic chain then the body will compensate when we begin to execute closed kinetic chain.

A classic example is a hip dominant strategy instead of a knee dominant strategy during squatting following an ACL reconstruction rehab case. The hip dominant strategy is often a result of a weakened quad and the body self-regulating to avoid loading the knee. The best way to isolate quadriceps strength is open kinetic chain.

From a psychological perspective, athletes will regain confidence quicker if they can demonstrate to themselves that they are able to move the joint or load the injured tissue. Single joint, open chain actions help restore this confidence quicker.

6. Position

More contact points -> Less Contact Points

What’s more physically challenging, standing on one leg or being on your hands and knees? Standing on one leg you have 1 point of contact with the ground and being on your hands and knees you have 6 points of contact (2 hands, 2 knees, 2 feet).

Position allows me to manipulate exercises within sessions and day to day plans. For example, with a knee rehab case we can start the athlete in a prone bear position (hands and feet) before we progress them to a standing Smith machine squat. Both positions are challenging the squat, but the prone bear manipules ground contacts and gravity to reduce the demands placed on the knee.

Underlying principles in this Performent are gravity, degrees of freedom, and the neurodevelopment model of human development.

7. Assistance

Passive -> active assisted -> Active -> Resisted -> Resisted Assisted

Passive range of motion is the equivalent of “I am going to move this leg for you.” Active assisted is then “We are going to move this together.” Active will be when the athlete can move their leg independently. Resisted begins to add load and create tissue overload. And the final phase of resisted assisted is the use of resistance to overload speed or deceleration (I typically use resistance bands as a mean of pulling an athlete into a cut or deceleration.)

Each of these phases gradually reduces the therapist’s or coach’s assistance to promote independence during the return to play process. The analogy we can think of is riding a bike. The beginning phases the athlete is riding in the side car as the therapist is pedaling the bike. Then eventually the athlete begins to ride the bike first with training wheels then without. The final phase is they are riding downhill achieving speeds they would not be able to create on their own.

8. Anticipation

Planned -> Reactive

In my early career I was a youth and college soccer coach. I really enjoyed the aspects of motor learning classes in my undergraduate curriculum. I utilize anticipation later in the return to play process and certainly creates an added progression within many different phases.

Planned anticipation is when the athlete knows exactly what they are about to do. It is the equivalent of you being given a specific recipe for dinner and you simply need to follow each step to cook a delicious dinner. Planned anticipation allows for the athlete to be in control of their movements. In the context of sports, most offensive plays are planned anticipation.

Reactive anticipation is when the athlete is not aware of exactly what they are suppose to do. They will have a general idea but the specifics will not be determine until the last second. This is sport. This is what separates the best from the rest. The ability to react quickly challenges not only the cognitive demands but also the speed of movement. In sport the reactive anticipation often times occurs in defensive plays where the athlete has to react to their opponent.

9. Ground Contact Times

Long (extensive) -> Short (intensive)

Ground contact times refers to how long the foot is in contact with the ground. The length of the ground contact time suggests the intensity of the movement. Shorter ground contact times suggest increases in intensity, velocities, and overall outputs. This Performant applies to multiple vectors including linear (sprinting), vertical (jumping), and lateral (change of direction).

Long ground contact times are a way to build capacity and volume. I also label this as extensive conditioning. Lower speeds and lower intensities have an inverse relationship with higher volumes. The opposite is true for higher speeds and intensities, which have an inverse relationship with lower volumes.

A quick example is I will begin an athlete with sled pushing (very long ground contact times) before I progress to marching/skipping before I progress to running and sprinting. Each phase I reduced the ground contact time to ultimately increase the intensity of the action to get closer to the demands of sport.

10. Small Sided Games

Smaller spaces -> Bigger spaces | Fewer Players -> Many players

Smaller spaces of games and drills demonstrate higher deceleration and acceleration counts, but the size of the space limits the intensity of velocities. Larger spaces create opportunities to accelerate longer and create higher velocities and intensities. Think about a 40 meter dash versus a 100 meter sprint. The 100 meter sprinter will achieve a higher velocity than the 40 meeter dasher simply because they have more space to continue to accelerate.

Small sided games is well researched in sports such as rugby and soccer. Additional insights from the research indicate that smaller spaces produce more neuromuscular and strength adaptations while larger spaces produce more aerobic and speed adaptations. For example, in basketball, 1v1 in small spaces in comparison to 5v5 full court will produce lower velocities but higher volume of accelerations and decelerations.

My preference is to continue to challenge strength and neuromuscular capabilities before I progress to intensive aerobic and velocity demands.

Summary

The 10 Principles are my framework for how I progress the gray space of rehabilitation and return to play. Yes, I do use objective testing such as peak velocities, peak torque, and force plate data as part of the process too. I think as an industry we have gotten very at the objective piece, but often times its the gray space that makes or break a rehab case.

What do you think of The 10 Principles? Any more you would add or adjust? Leave a comment or reach out over social media!